Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio appeared on the cover of the May 22-29 issue of Time magazine, with the headline stating that Kishida “wants to abandon decades of pacifism – and make his country a true military power.” Uncomfortable with the text, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an objection to the publication. The ministry said that the wording used by Time on the cover – particularly the reference to Japan as an aspiring “military power” – did not reflect the general tone of Kishida’s interview.

Intuitively, considering the amount of money that Japan is planning to allot to its defense budget, the characterization of it as a military power seems accurate. If the Japanese budget continues to balloon, according to Kishida’s pronounced plan last December, Japan would become the world’s third-largest military spender. In fact, taking into account that Japan currently has the ninth-largest military expenditure among all countries, describing Japan as not only an aspiring military power, but even an already established one seems not so distant from the truth.

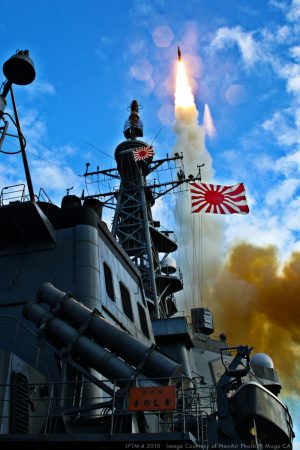

However, due to Japan’s unique political culture, its politicians and policymakers need to be extra cautious of how they deploy language surrounding military affairs. In fact, Japan resists using the term “military” at all – its armed forces are officially the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

In Japan, pacifism is a dominant force that dictates both domestic and foreign policy and penetrates the social fabric of the nation. The country’s wartime past as both an aggressor – committing atrocities and invading neighbors across the region – and as a victim – being bombarded by the allied powers according to their scorched-earth policy, culminating in the two atomic bombings – immersed the public in a deep sense of remorse and hesitancy toward any military-related subjects. The pacifism rooted in those experiences is embodied in Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, which states that “the Japanese people forever renounce war” and pledges that “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.”

Deeply sensitive to setting a precedent for militarism to revive, the Japanese public had been extremely reluctant to dispatch troops abroad, even for peaceful purposes, mindful of Japan’s past as an aggressor state and fearing foreign entanglement. The attitude of the public has softened to some extent, following the criticisms following the Gulf War in 1991 that Japan’s offer of financial support alone to the allied forces was “too little, too late.” Yet even today, whenever the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) are dispatched for peacekeeping missions there are rigid requirements on the circumstances under which they can use force, even for defense purposes.

The Japanese people have been attentive – even proud – of their image as a pacifist nation. Any indication that they aren’t one – as the cover of Time magazine seemed to suggest – touches a nerve. The government felt public pressure that compelled them to implore the magazine to refrain from the usage of the term “military power.” It was subtracted from the headline in the digital edition.

However, the notion that Japan has been a pacifist nation all along is mythologized to a great extent, considering that the country began to formulate the framework for its military by another name from the earliest stage of the post-war pacifism. Less than five years after Japan adopted its pacifist constitution, the United States demanded that the Japanese government remilitarize in 1950, in order to compensate for the U.S. forces that were dispatched to fight the Korean War. That pushed Japan to create the Self-Defense Force in 1954. Critics at the time described Japan’s immediate remilitarization process as a “reverse course,” implying Japan was deviating from the pacifist direction that they were supposed to follow – a criticism that is oddly similar to the criticisms raised by the Time magazine controversy today.

Moreover, at the end of the 20th century, thanks to Japan’s then-booming economy, its military spending reached the second largest in the world, surpassed only by the United States, the world’s largest military power. Nonetheless, despite Japan being a de facto military power, in terms of the size of the budget and the capability of its military assets, the Japanese people fail to recognize – or intentionally disregard – the reality that they are in fact a military power.

While the Japanese people continue to have a strong attachment to pacifism, the government has been slowly and quietly shifting the country to a war footing, hastened by their realization of their worsening security environment. However, the government has stalled their efforts for fear of a backlash from public opinion. Mainichi Shimbun had reported that the United States’ installation of long-range cruise missiles on Japanese soil was rescheduled due to Japanese objections that such an endeavor faced “high political hurdles,” considering public sentiment.

Moreover, although Japan is planning to develop indigenous long-range missiles, considered as a necessity for deterring China, the ultimate deployment is expected to come in the 2030s. Given the warning of security experts that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would likely take place before then, the interregnum for the deployment of long-distance striking capabilities seems excessively prolonged.

In fact, even if Japan becomes militarily prepared to engage in a war defending Taiwan, there is a real possibility that the public would not allow any involvement, a sense that is reflected in recent polls. According to a poll published by Asahi Shimbun, more than 80 percent of the population answered that the SDF should not be militarily engaged with China to defend Taiwan, in contrast to only 11 percent who supported such an endeavor in concert with the U.S. military. Out of the 83 percent who refused to send the SDF into harm’s way, 27 percent of the respondents answered that Japan should not collaborate with the United States at all under such a scenario.

As a recent wargame from the U.S.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies indicated, it is imperative for the United States to use bases in Japan to successfully defend Taiwan. However, if Japan decides to become a bystander in a potential military conflict between the U.S. and China, which looks like the preferred scenario for at least some portions of the Japanese public, U.S. efforts to defend Taiwan would face severe hurdles – possibly rendering the United States, too, a bystander while Taiwan fights alone against China.

Regarding the perception of whether their country ought to be a military power or not, the widening gap between the Japanese government and the general populace has significant geopolitical consequences. If the government fails to convince the public to assume the burden that corresponds with the defense build-up, the ultimate result – likely a successful Chinese invasion of Taiwan – would upend the balance of power in East Asia.

Although the majority of the Japanese public certainly does not recognize the fact, the fate of the international order is dependent upon how the Japanese public deals with a Taiwan contingency. However, whether they will be able to proactively influence that outcome will require the government to embark on the task that they are afraid to take on – to recognize that Japan is in fact a military power.