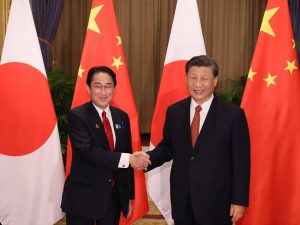

On November 17, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met in Bangkok, Thailand, on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit. This is the first in-person meeting between the leaders of Japan and China in almost three years. The COVID-19-related travel restrictions imposed by both countries may have contributed to the long gap between meetings, but it is also true that Sino-Japanese relations were cool during this time period.

While both Kishida and Xi have used virtual means of communication to speak with other world leaders, this is also the first conversation between the leaders of the two countries since Xi made a brief congratulatory call in October 2021 when Kishida took office.

At the meeting, the two leaders agreed on the importance of stably developing bilateral ties. To advance that goal and maintain communication, they decided for Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa to visit China.

Other areas of agreement were also predictable: the two sides opposed Russia using nuclear weapons in Ukraine and agreed on the need to cooperate in the economic sphere and on climate change. However, as widely expected, they did not reach any agreement regarding the issues that could derail strong bilateral ties, specifically regarding Taiwan and the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

Japan had declared as early as 1969 in the joint statement by U.S. President Richard Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato Eisaku that “the maintenance of peace and security in the Taiwan area was also a most important factor for the security of Japan.” However, recent events have dramatically highlighted this point: When Beijing responded to U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan by conducting military drills around the islands, five Chinese ballistic missiles fell within Japan’s exclusive economic zone.

Regarding Taiwan, Kishida told reporters that “I reiterated the importance of peace and security in the Taiwan Strait.” But the road to a mutual understanding on Taiwan is still unclear, as according to CCTV, Xi responded to Kishida’s concerns over Taiwan by saying that “China does not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries, nor does It accept anyone interfering in China’s internal affairs under any pretext.”

Analysts and journalists have pointed out the domestic political challenges that Kishida faces in stabilizing relations with China. Takashi Nakagawa and Seima Oki wrote for Yomiuri Shimbun, “It seems Kishida is going to pains to strike a balance between reaching out to Beijing and staying keenly aware of domestic public opinion on China’s actions.”

A different Yomiuri article pointed out the contradictory wishes and concerns within the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito: “In addition to requests for continued constructive dialogue heard from some in the Liberal Democratic Party, conservative party members expressed concern about the rush to improve relations with China, which has increasingly moved to strengthen its hegemony.”

These challenges would exist for any Japanese leader trying to manage the expectations of a large party on a complicated issue, but Christopher B. Johnstone of CSIS pointed out why it is particularly fraught for Kishida, compared to late former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo:

Abe’s hawkish views and political pedigree – he hailed from a strand of the Liberal Democratic Party that historically favored a strong defense and closer ties with Taiwan – inoculated him from criticism at home for engaging China’s leaders, such as when he conducted a state visit to Beijing in October 2018. Kishida’s roots in the Kochikai faction of the LDP – traditionally more dovish and pro-engagement with Japan’s neighbors – afford him less insulation.

Survey experiments conducted by Michaela Mattes and Jessica L. P. Weeks confirmed the intuition undergirding Johnstone’s point. They find that “hawks are indeed better positioned domestically to initiate rapprochement than doves.” Mattes and Weeks also examined why this might be the case and conclude that (1) “voters are more confident in rapprochement when it is pursued by a hawk,” and (2) are more likely to view hawks who initiate conciliation as moderates. Forthcoming observational quantitative and qualitative work by Michael Goldfien reinforces the point that in democracies, doves are historically less successful than hawks at rapprochement.

Not only does Kishida have significant challenges ahead of him vis-à-vis China, any of his attempts to improve relations with China will likely be subjected to close scrutiny because of his dovish reputation. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as public accountability is a fundamental principle of democratic governance. However, the Japanese public should also give Kishida the opportunity to improve ties – even if there may be occasional false starts and some instances of two steps forward, one step backwards – without being so quick to criticize. Peace and stability is in the best interests of all peoples.