DILI, TIMOR-LESTE — “Munir was a genuine friend of the East Timorese people, and all other oppressed peoples across the region,” said Diamantino da Costa Freitas, a victim of the Indonesian occupation authorities’ abuses in what was once the Indonesian province of Timor Timur, and now the country of Timor-Leste. He was remembering slain human rights activist and lawyer Munir Said Thalib on the 14th anniversary of his death.

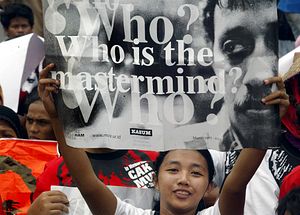

On September 7, 2004, Munir Said Thalib , Indonesia’s most prominent human rights campaigner at that time, was poisoned to death — allegedly on the orders of the Indonesian state intelligence agency BIN — aboard a Garuda Indonesia plane en route to Amsterdam. Munir was traveling to the Netherlands to study International Humanitarian Law at Utrecht University.

In 2005, Indonesia’s Supreme Court convicted former Garuda pilot Pollycarpus Budihari Priyanto of murdering Munir and handed down a 20-year sentence, which was later reduced to 14 years. However, on November 28, 2014, Pollycarpus was released on parole after serving eight years in Sukamiskin Penitentiary in Bandung and on August 29, 2018, he was officially declared a free man. Recently, he joined Tommy Suharto’s Berakaya Party, stirring outrage in human rights activists across Indonesia.

Human rights campaigners argue Munir’s murder can be traced to figures within the country’s intelligence community. Muchdi Purwopranojo, a senior official with the BIN, had been in frequent contact with Pollycarpus in the period surrounding Munir’s death and was also charged with the murder. But the South Jakarta District Court in 2008 acquitted him of all charges. Also implicated in the murder but never investigated was former BIN chief Abdullah Mahmud Hendropriyono, a close ally of former President Megawati Sukarnoputri and former chairperson of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). According to U.S. diplomatic cables leaked in 2011, Hendropriyono was involved in the planning of Munir’s assassination.

Freitas had met Munir in late 1999 — five years before the latter passed away — in Dili when Munir was visiting the island as a member of the Indonesia’s National Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights Violations in East Timor (Komisi Penyelidik Pelanggaran HAM di Timor Timur, or KPP-HAM). The commission was tasked with investigating the human rights violations and abuses perpetrated by the withdrawing Indonesian forces after the East Timorese massively voted in favor of Timor-Leste’s independence in a UN-monitored referendum held on August 30, 1999.

“Munir was calm, composed, and very soft-spoken. He listened to our stories very carefully. He had a lot of empathy for us; he knew what it meant to be without the basic human rights and what a massive tragedy we had been through. He understood the sufferings of the East Timorese,” said Freitas.

Munir started off his career as a rights activist when he was studying at Brawijaya University in Malang, East Java. After graduating from the university, he joined the Legal Aid Foundation as a lawyer. In the early years, he was involved in labor advocacy and also played some significant roles as a lawyer striving for justice in certain military-linked cases, such as the 1993 murder of unionist Marsinah and the 1993 Nipah land dispute in Madura.

In 1998, Munir founded Commission for “the Disappeared” People and Victims of Violence (KontraS), a human rights organization that demanded justice for victims of state abuse and started exposing crimes by the Indonesian military and militias in East Timor in 1999.

Thus, many believe, Munir had over the years become a thorn in the military’s side, which prompted his assassination.

A Former Exile Refuses to Forget the Past

Domingas de Araujo Mendonca is a gardener and flower seller in Dili, and today she looks like any other random street vendor squatting by the streets in the sprawling coastal capital of Timor-Leste. But three decades ago, when she was only 17, she was already a battle-hardened Fretilin guerrilla fighting for the liberation of Timor-Leste from the yoke of Indonesian occupation that lasted from 1975 to 1999.

In 1982, she was captured by the Indonesian military and exiled to Atauro Island for two years.

“I was a member of the clandestine resistance movement. When I was captured by the Indonesian military, I was 17. They tortured me for several months. I was stripped and forced to sit in water tanks, given electric shocks, and sexually abused. Then I was banished to Atauro Island,” said Mendonca, who also testified before the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste (CAVR), a truth commission formed to “inquire into human rights violations committed on all sides, between April 1974 and October 1999” in Timor-Leste.

Atauro Island is located 18 miles off Dili on the western Pacific Ocean. During Portuguese colonial times, Atauro served as a notorious prison, housing exiles, prisoners, and dissenters from Portuguese colonies across the world, such as Mozambique, Angola, and São Tomé and Príncipe in Africa; Portuguese holdings like Goa in Asia; and Portugal itself. The Indonesians also used the island as a penal colony, as a place to banish captured Timorese resistance fighters, sympathizers and their relatives. It was considered a hellhole for detainees.

Mendonca and her fellow exiles were forced to work on a road on the island, the women collecting rocks from the coast as the men broke them up. Mendonca recalled, “We had to break our backs to work for food and drink. The food we were offered was scant and it was of the worst quality. Those were the toughest days of my life.”

After being released in 1984, she settled down on a vacant plot in a corner of Dili and started gardening and selling flowers for her livelihood. Today she feels her suffering has been forgotten by others. “The bitter experiences I and hundreds of other women like me had had are unforgettable for us. I refuse to forget,” she said. “Our country is now independent, but no government official has ever showed up in my door to ask me about my plight. The hope of getting justice for the sufferers like me is fast slipping away.”

Mendonca, however, remembers Munir as “one of the few Indonesians who lent support to the East Timorese cause. He spotlighted forceful disappearances, detentions, and banishment by the Indonesian authorities in East Timor and elsewhere in Indonesia under Suharto’s military-backed New Order Regime.

“I’d love to see justice delivered to his family.”

Justice for Munir, Justice for Timor-Leste

Even 14 years after the assassination of Munir and 20 years into Indonesia’s Reformasi era, resolving Munir’s case still remains an unachieved litmus test for successive governments in Jakarta, casting doubt over their commitments to delivering justice for past crimes and human rights violations.

Usman Hamid, a former colleague of Munir in KontraS and now the Indonesia director of Amnesty International, is of the view that the Reformasi has failed on human rights in Indonesia. Despite the status of the government, whether military or not, former police and military generals implicated in past human rights violations have continued to hold power in the past 20 years.

Notwithstanding governments’ efforts to do better on human rights in the post-Suharto era, the military, which still had considerable political influence in the parliament, under former President Abdurrahman Wahid’s managed to insert an article in the Indonesian constitution endorsing the legal principle of nonretroactive law enforcement. This effectively prevents future administrations from prosecuting the military for its past human rights violations, including the killings of around 200,000 people from 1975 to 1999 in Timor-Leste, according to Hamid. “This was where the Reformasi officially gave birth to impunity,” he said.

Timor-Leste, a tiny fledgling country, on the other hand, can’t afford to bear the diplomatic cost of estranging Indonesia, its former subjugator and currently largest neighbor and trade partner, by pushing for stern action in international platforms against Indonesia’s generals, military elites, and politicians involved in past crimes on its soil.

Nevertheless, in 2017, Timor-Leste’s prominent writer Dadolin Murak wrote a poem titled Jendral in Bahasa, which speaks to the long history of human rights violations in both Indonesia and Timor-Leste. The poem ends with a call for solidarity with Indonesian activists, echoing the solidarity Indonesian activists like Munir had expressed for Timor-Leste back in the 1990s. Murak said, “I wrote the poem to express my solidarity with the victims of the 1965 tragedy and the ongoing Indonesian human rights struggles. For me, fighting for human rights should transcend national borders.”

In the same vein, Freitas said, “A large part of Munir’s works pertained to Indonesian authorities’ rights violations and state abuses in East Timor, Aceh, and Papua and crossed the boundaries of mainstream Indonesian society. So justice for Munir also means justice for us.”

Meanwhile, Suciwati, Munir’s widow, has been continuously disappointed by the Indonesian justice system and has stopped pinning all her hopes on the legal process. Rather, she now looks to achieve what is possible on a social level, such as the launching of Omah Munir, a museum dedicated to Munir’s memory in East Java’s Batu city. She helped found Omah Munir in 2013 with the help of Munir’s former colleagues and friends. One central aim of the museum is to educate people on human rights, which could help foster a better sense and appreciation of human rights in Indonesian society.

“Melawan lupa — oppose forgetting — is our motto,” Suciwati said. “Munir is a single chapter in the bigger picture of the long struggle for human rights in Indonesia. I don’t want people to forget this struggle. Omah Munir aims to resist forgetting the Indonesian human rights struggle and its crusaders including Munir.”

Reporting for this story was funded by a Reporting Right Livelihood grant from the Sweden-based Right Livelihood Award Foundation.

Bikash Kumar Bhattacharya is an independent journalist based in northeastern India. His work has appeared in Buzzfeed, Mongabay.org, Down To Earth, The Diplomat, The NewsLens International, Scroll.in, Earth Island Journal, and Eurasia Review among other publications.