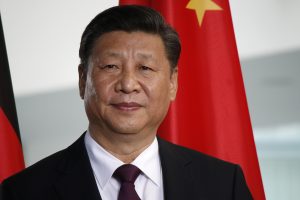

China’s top leader Xi Jinping is poised to secure a third term as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in October. That will break recent precedent and cement Xi’s reputation as a strongman leader and the center of a growing personality cult.

At this crucial time, it’s more important than ever to understand who Xi is and where he came from, all of which can help us better grasp the direction in which he is leading China. That’s the task undertaken by Stefan Aust and Adrian Geiges in their new biography of the Chinese leader, “Xi Jinping: The Most Powerful Man in the World.” Aust and Geiges conducted an interview with The Diplomat via email to discuss major takeaways about Xi’s life – and Xi’s China.

You mention several times in the book that Xi is more myth than man in China, “untouchable” as a subject. Did that make it difficult to do research about China’s “core” leader?

In some ways yes. It would be impossible to interview him personally; he doesn’t even give interviews to the Chinese media. On the other hand, it is one of the peculiarities of socialist countries that the collected speeches of the leader of the state and party are regularly published as books so that the “masses” can “study” them. We analyzed these writings, which resulted in a fairly complete world view of Xi.

Also, before he became president and “untouchable,” there were many publications in Chinese newspapers about his life – also because his wife Peng Liyuan is a singer, as famous in China as Beyoncé or Jennifer Lopez in the United States. These publications, nearly forgotten in China, became an important source for us.

When Xi first came to power, many Western scholars argued that his experience of family persecution during the Cultural Revolution would make him more moderate or liberal-minded. The opposite seems to have been the case, however – Xi strove to present himself as “even more revolutionary” and “even more communist.” Can you summarize Xi’s transition from victim of CCP excesses to “redder than red” party member?

Well, this transition of Xi Jinping is a crucial topic of our book and of course cannot be summed up in a few words. But to mention a few aspects: Xi witnessed his father being imprisoned and tortured during the Cultural Revolution and did not want to suffer the same fate. So he took Mao as a model. He had previously fled the village to which he was exiled when he was 15, but his relatives, all convinced communists, persuaded him to go back: Even in difficult times one must follow the party. He also saw China’s backwardness in the village and consciously chose a political career to change that. And in China that is only possible in the Communist Party. He later followed the political developments that led to the end of the Soviet Union and the war in Yugoslavia. This taught him: If the party relinquishes power, the country will plunge into chaos and war.

Deng Xiaoping was instrumental in the political rehabilitation of Xi’s family, and in the making of modern China. Yet some scholars argue that Xi has led a campaign to downplay Deng’s contributions to China’s modern success, elevating Xi’s father (and, by extension, Xi himself) instead. What’s your take on Xi’s approach to Deng Xiaoping’s legacy?

Absolutely right, Deng Xiaoping, whose reform and opening up made China wealthy, is increasingly being relegated to the sidelines. We would doubt that he will be replaced by Xi’s father, Xi Zhongxun, who was also in fact a reformer. In November 2021, the Communist Party’s Central Committee had passed a resolution about the party’s own history. The document mentions Deng Xiaoping only six times, Mao Zedong 18 times, but Xi Jinping 24 times.

Xi Jinping is still talking about reform and opening up, but in fact he is taking it back. He has now completely isolated China from the outside world – under the pretext of COVID-19, but mainly because it suits him politically.

Xi Jinping is widely known abroad for his “cult of personality.” Other leaders have not pursued such personalized adoration, at least not to this extent. What made Xi different?

One of the lessons of Mao’s crimes was that such a personality cult should never be repeated. Instead of displaying his body in a mausoleum, Deng Xiaoping had his body cremated and the ashes scattered over the sea to avoid creating a place of worship. The terms of office of Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, were limited to two five-year terms. Xi changed that for himself. The personality cult surrounding him is becoming more and more grotesque. For example, zealous provincial officials have been demanding that Christian churches replace images of Jesus with portraits of Xi Jinping.

For one, Xi sets himself apart by allowing such a cult to spread around him. On the other hand, his campaign against corruption and his tough stance toward foreign countries have made many Chinese believe him to be a strongman who stands up for the Chinese people.

There has been much discussion abroad of Xi’s ambitions for his legacy, particularly in the context of Taiwan these days. Xi has set out a large number of goals for China’s “new era,” from anti-corruption to poverty alleviation; from making China into a “world-class” military power to the Belt and Road Initiative. Which goals do you see as most crucial to Xi on a personal level, given his background?

According to Xi Jinping’s own words, by 2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic of China, his goal is to make China the world’s leading power – and not just economically. But what does that mean in concrete terms? It has to be feared that it will end up conquering Taiwan and other islands as his main legacy. And that would not mean worldwide development, as promised by the Belt and Road Initiative, but a worldwide catastrophe, in the worst case a world war.