In China’s tightly controlled party-state, the non-party institutions are facades aimed at preventing any independent organizational efforts, but they are also affected by tensions between consensus-building and concentration of power among the ruling elites.

The “Two Sessions” ritual has been celebrated every year since 1993 in early March. Arranged down to the smallest detail, the annual event has given the Chinese public a sense of stability that is highly regarded, even if its role is mostly decorative.

The “Two Sessions” custom centers on the annual national sessions of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). The NPC is China’s rubber-stamp parliament. The CPPCC’s role is harder to define.

The History and Purpose of the CPPCC

The CPPCC in its heyday served as a kind of constituent assembly providing a provisional constitution (Common Program) for the newly created People’s Republic of China, and establishing governmental institutions for the transition period between 1949 and the promulgation of the constitution in 1954. During this time, the CPPCC issued nearly 3,500 laws that laid the foundations for the PRC state-building measures. In 1954, in the wake of establishment of the NPC, it transformed into a top-level assembly for satellite political parties and all kinds of official organizations that were affiliated with the United Front Work Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The continuing existence of the CPPCC alongside the NPC wasn’t assured, and is an example of both the importance of precedent and the flexibility of CCP organizational practices. It also proves that for repressive regimes powerless and vaguely defined institutions are a valuable platform for controlled state-society encounters.

In 1954 Mao together with other Chinese leaders, despite already well-established control over society, decided to keep the CPPCC as a powerless, but useful, tool that provided the groups not directly under party control with an organizational platform that facilitated official contacts. The redefined CPPCC’s attractiveness lies in its enhanced prestige and easier access to China’s power centers. Its members became officially recognized as “political advisers,” although the exact meaning of the term remained only vaguely and imprecisely defined.

The possibility to send delegates under the banner of licensed organizations was especially important, because the structure of the newly created NPC did not allow for the creation of any parliamentary circles besides those along the provincial lines. The CPPCC, by contrast, is divided into parties, societies, “groups” and “sectors.”

The NPC, even in the form of a “rubber stamp,” was nevertheless granted power to enact new laws, and as such demanded stricter control and domination by the CCP. The CPPCC, devoid of any serious responsibility, was meant to entice those still wary of the CCP’s dictatorial methods – including intellectuals, artists, businessmen, ethnic minorities, religious leaders, and overseas Chinese – as an institutional solution that enabled those who recognized the leading role of the CCP to participate in political activities without the party affiliation.

Even so, the need for overall control by the CCP demanded that the party itself, its affiliated organizations, and CCP members in all other groups dominate the agenda.

The willingness of the CCP leadership to preserve the institutional continuity of the CPPCC through the vaguely defined role of “political advisers” stemmed from remnants of the “united front” tactics, still fresh in 1954. China’s leaders recognized the need for a some restrained form of representation of diverse social and political groups. But give the way that events evolved, with the radicalization of policies and internal struggles among PRC leadership, the CPPCC concept was soon detached from reality. Putting aside some efforts in the early 1960s to revive the organization, the Cultural Revolution successfully got rid of it, as with so many other institutions. (Even the NPC was convened only once during those tumultuous years, just to promulgate the new Maoist constitution in 1975.)

In the post-Mao era, the reestablishment of former institutional arrangements became a political statement that defined the Cultural Revolution period as an anomaly, which should be put into parentheses. The revival of the CPPCC was thus beyond question, its importance assured by the new chairman Deng Xiaoping (Zhou Enlai had been the first one), and the following ones, Deng Yingchao and Li Xiannian, both CCP heavyweights.

The CPPCC: Open for Business

The reform and opening period also revived united front tactics and confirmed the need for seeking broad-based social support. The new rules of the CPPCC issued in 1983 set the upper limit of CCP members at 40 percent, a limit that has been respected since then. The membership was roughly doubled from less than 1,200 in 1965 to nearly 2,000 in 1978 and slightly more than 2,000 from 1983 onward.

In the post-Mao era, the CPPCC also got an important new function: attracting investment funds from overseas Chinese communities. It became a foremost institution for accommodating Hong Kong and Macao elites in preparation for reunification, when in 1983 a new “sector” was created especially for them.

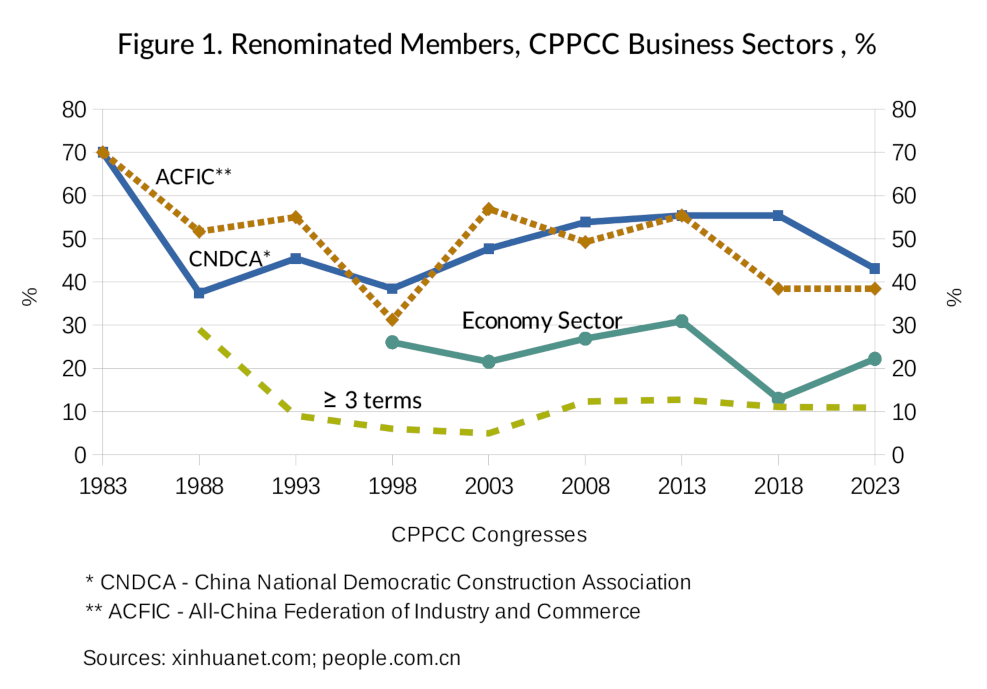

Traditionally, the China National Democratic Construction Association (CNDCA), one of the satellite parties, and the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce (ACFIC), an umbrella organization for all kinds of business associations, were the two CPPCC sectors regarded as business representatives. In the 1990s, when the social standing of entrepreneurs was enhanced and confirmed by the official policies, a new “Economy Sector” was created inside the CPPCC, and successful businesspeople also started being elected as NPC representatives.

The growing importance of business circles in the CPPCC was confirmed by the increased numbers of their members. In 1965, both the CNDCA and the ACFIC had 40 representatives each. In 1978, the number was increased to 50, then in 1988 to 64 and 60, respectively, and from 1998 to 65 each. The Economy Sector has been fluctuating more, climbing from 83 representatives in 1993 to above 100, then around 150 from 2008 to 2013, before decreasing to 108 this year (the smallest representation since the formative period).

The spectacular economic growth fueled by private enterprises created numerous groups of resourceful businesspeople that were increasingly seeking official forms of communication and support within the administrative party-state apparatus, as well as an opportunity for enhanced networking strategies. CPPCC assemblies at all levels became an attractive institution that was especially accessible to those who, as entrepreneurs, were systematically denied party membership.

After the official confirmation of an ideological shift in 2002, when the theory of “Three Represents” allowed businesspeople to apply for CCP membership, there were more options and directions for networking strategies. The CPPCC’s attractiveness didn’t diminish, but was rather enhanced by the growing possibility of being entangled in a network of alternate membership at every level of both the People’s Congresses and Consultative Conferences. Recommendation of candidates by business associations, the CCP, and the satellite parties enabled resourceful entrepreneurs many alternative ways to get nominated (to the CPPCC) or elected (to the NPC).

The Rise and Fall of Networking

Hu Jintao’s rule between 2002 and 2012 was characterized by internal rifts, infighting and factional struggles inside the party-state apparatus and the dynamics it created extended for another couple of years. That created the right environment for the peak of entrepreneurs’ engagement in the NPC and CPPCC in the decade between 2008 and 2018.

The tensions inside the party-state’s administrative institutions resulted in an increased need for factions to seek coalitions with rich business elites and other local leaders to promote projects that met with resistance in other parts of the bureaucracy. Such rifts became the fertile ground for all kinds of formal and informal networking strategies, actively sought by all parties. The centralizing efforts of Xi Jinping became only gradually apparent after 2012, and didn’t at first affect the spectacular rise of Chinese giant internet firms, and as a consequence a very visible participation in both the NPC and the CPPCC by their owners.

The golden age of national assemblies’ networking opportunities, as well as the relatively open attitude inside bureaucratic structures toward formal proposals voiced by important business leaders in their capacity as assembly members, came to a symbolic end in the fall of 2018, just half a year after the 13th terms of the NPC and the CPPCC began.

The Central Committee of the CCP in October of that year issued a document titled “Several Opinions on Strengthening the Party Building in the CPPCC in the New Era,” which emphasized the importance of party control over all the activities inside the institution, as well as the need to strictly follow the guidelines of the CCP leadership with “Xi Jinping as its core.” The wording of the document was a direct challenge to the institutional developments of the CPPCC at least from 2003 onward – that is, the networking practices based on intra-bureaucratic tensions and formulation of petitions that were independent from official policies. The document left little room for any autonomous activity.

In this sense, it contradicted the spirit of the reform and opening era, when by introducing a 40 percent upper limit for CCP members in the CPPCC, the then-party leadership gave a clear signal that total domination by party structures over all kinds of institutions is counterproductive for the rule of the party itself. The message the document of the “New Era” conveyed was need for more control by the party leadership.

The new circumstances don’t prevent all possibilities of networking, but significantly change their nature and take away much of the appeal that both the CPPCC and the NPC offered to Chinese entrepreneurs in the last two decades. The need for communication channels with the world of officials, as well as good positioning in the never-ending subsidy games, will not disappear, but influencing the decisions made at the highest administrative levels has become much less probable.

The current worries and doubts among many of China’s entrepreneurs about the government’s attitude toward the private sector were unwittingly confirmed during the 2023 Two Sessions by Wang Yu, chairman of Spring Airlines and a renominated CPPCC member. After a meeting between Xi Jinping and the business sectors of the assembly, in which the nation’s leader assured of his “unswerving support” for private firms, Wang stated that Xi’s remarks helped “eliminate any worry among the vast number of private entrepreneurs and set our minds at ease, and greatly boosted our confidence in continuing to overcome difficulties.”

Looking to the Data

Analysis of aggregated data concerning business representation and networking strategies in both the NPC and the CPPCC confirms the trends described above and adds more depth to the story. One of the most obvious aspects of a representative’s success is reelection. Networking abilities are also greatly enhanced over time by growing familiarity with the system. The five-year terms are long enough even without reelection for efficient networking in crucial times for business development, but a second term means a whole decade in an official position of prestige and influence. Two terms can thus be treated as a standard attribute of an accomplished representative, while three terms and above are an indication of a special status of old-timer, with numerous and long-term connections to the officials.

Since the NPC does not have official functional representation – instead, its members represent provinces and localities – selecting business representatives is difficult and uncertain. In the CPPCC, sectoral representation is well defined, but to some extent also inconclusive, because the boundaries between sectors are not clear and members often represent different ones during consecutive terms. Entrepreneurs can be found encounter in nearly all of them. Nevertheless, most business representatives are gathered in the three sectors: the China National Democratic Construction Association, a satellite party dominated by business circles; the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, and the Economy Sector. (Additionally, most of Hong Kong’s billionaires are usually placed in the “Specially Invited Hong Kong Personages” sector, but that is excluded from the data analyzed in Figure 1, as it is not specifically business oriented.)

As shown in Figure 1, the renomination rate in the reform and opening era has been kept, with some exceptions, between 40 and 60 percent for the institutionalized sectors (CNDCA and ACFIC) and visibly lower for the Economy Sector. The representatives with three terms in office and above, although not so numerous, have been maintaining themselves on a stable level above 10 percent from 2008 onward.

The CNDCA and ACFIC’s renominated members between 2003 and 2013 constituted around 50-55 percent of their representation; then in 2018 the ACFIC rate dove below 40 percent, one term before the CNDCA renomination rate adjusted to a similar level of slightly above 40 percent. Also the Economy Sector experienced a sharp decline in the renomination rate from 31 to 13 percent in 2018, before rising back to 22 percent this year (a level still significantly lower than in 2013).

The lower renomination rate, especially in institutionalized sectors, can signify that in Xi’s tenure the leadership became less tolerant of allowing business representatives extended periods of interaction with the official world. The Economy Sector’s low renomination rate is also indicative of the ad hoc and temporary nature of such assignments when there are no places available or suitable in institutionalized sectors. Moreover, the diminishing levels of renomination in all business sectors can also mean we are seeing a period of major adjustments in networking business circles that in the long run could produce new groups of entrepreneurs who are equally successful in maintaining official positions for longer periods.

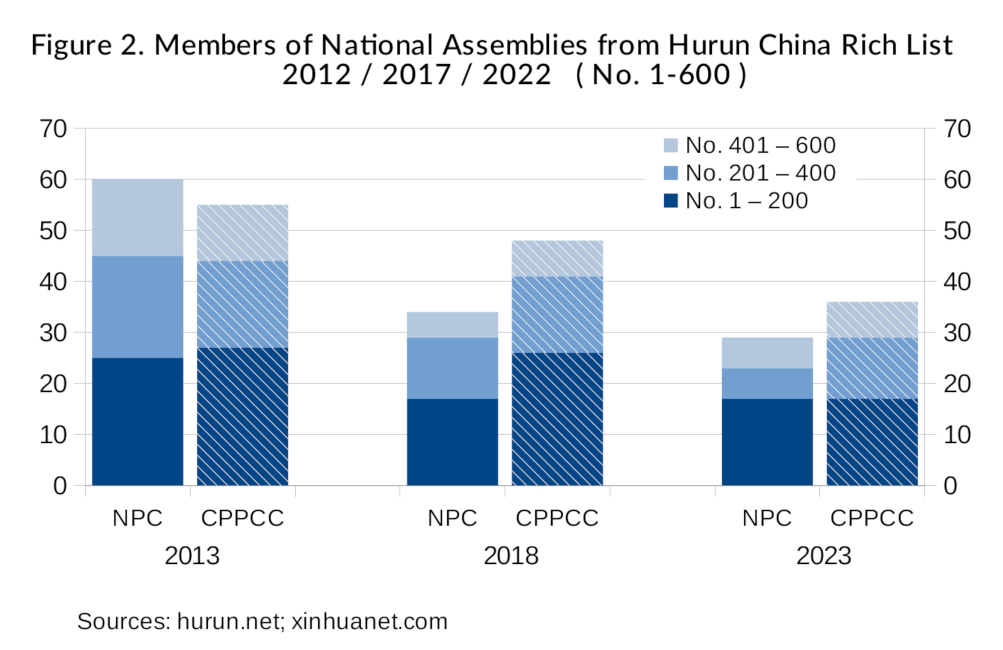

The analysis of data concerning participation in both the NPC and CPPCC by entrepreneurs occupying the top 600 positions on Hurun’s “China Rich List” confirms their diminishing presence in both bodies. The membership is counted according to the China Rich List from 2012 for the term 2013-18, list from 2017 for years 2018-23, and from 2022 for the current term (Figure 2).

From 2013 onward, there is a visible drop in the presence of the richest Chinese in both the NPC and the CPPCC. The biggest fall – a drop of nearly 50 percent – happened in the NPC between its 2013 and 2018 terms. In 2013 representation of the richest Chinese in the NPC was more numerous than in the CPPCC; afterwards the CPPCC took the lead. In the NPC the sharp decline in 2018 was followed by a much smaller one in 2023. In the CPPCC the biggest drop appeared in 2023.

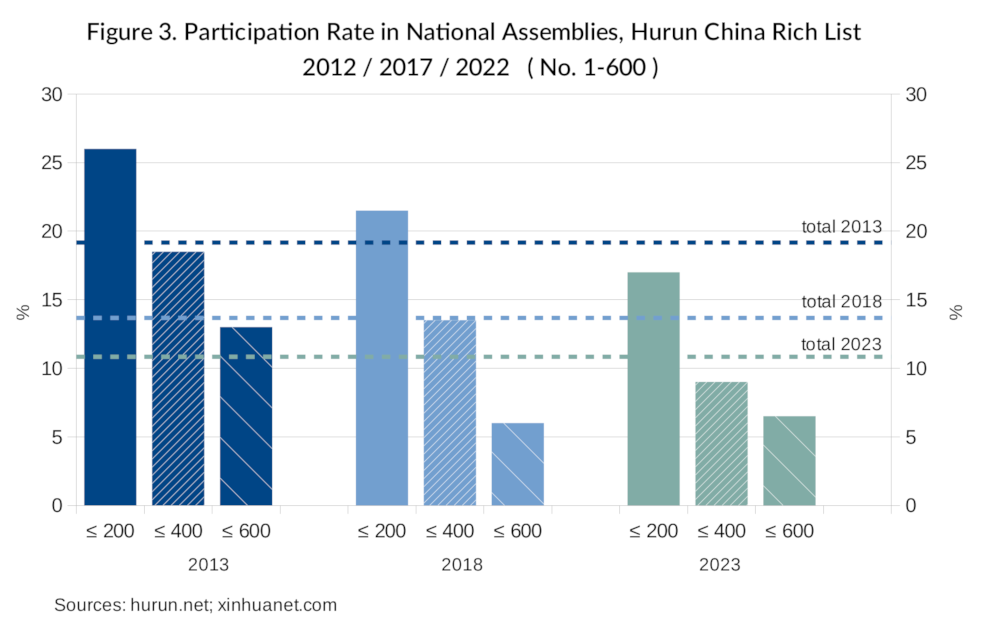

Interestingly, the top 200 wealthiest individuals had the best chance of making it into the NPC and the CPPCC, a trend maintained for all three terms (see Figure 3 below). The diminished participation is therefore most visible in the two lower analyzed groups of the Hurun list (those ranking between 201-600).

The biggest drop in the overall list’s representation in the NPC and CPPCC, from 19 to 14 percent, happened in 2018, but the trend was confirmed this year by another decrease to 11 percent. The presence of top 400 leading personages from the Hurun list diminished steadily, whereas for those ranked between no. 401 and 600, 2018 was the year of the biggest decline. The rate fell from 13 percent in 2013 to 6 percent in 2018, where it remained this year.

Distinguishing between the reelected or renominated members and the new ones allows some room to argue for the existence of a moderate tendency to reshape a group of business representatives in Xi Jinping’s era. But any confirmation of this trend will come only in the following terms, and the diminished representation of the richest entrepreneurs seems set to stay.

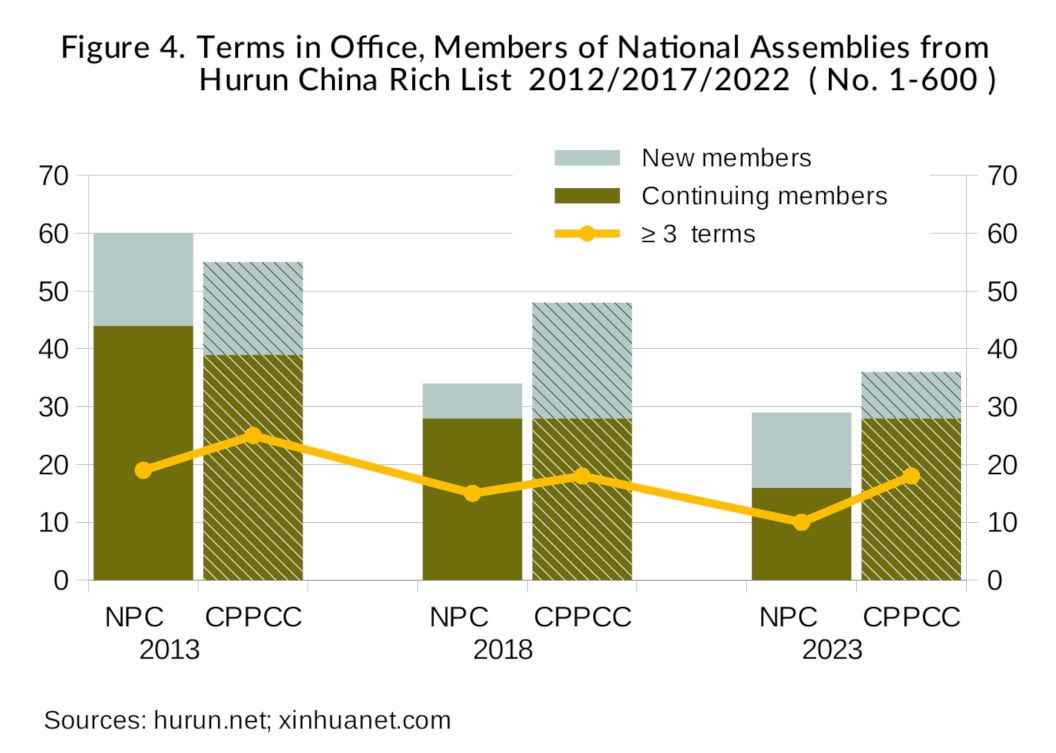

The results presented in Figure 4 indicate that the majority of the richest Chinese in both the NPC and the CPPCC in 2013 were the reelected/renominated ones (73 and 71 percent respectively) and there was a significant number serving at least a third term (32 and 45 percent). Then in 2018 the patterns for the NPC and the CPPCC diverged, with diminished representation in both.

In the NPC the domination of the richest members with previous experience in the office became even more pronounced (82 percent), as there were very few new faces. In contrast, the rate of new members in the CPPCC increased to 42 percent. And the overall decline of participation levels was much smaller in the CPPCC than in the NPC.

The pattern became reversed this year, when new members from Hurun list in the NPC rose to 45 percent, and the overall representation rate declined slightly. The decline of the richest Chinese this year was more pronounced in the CPPCC, and the vast majority were renominated (78 percent) with very few new faces in that assembly.

It is worth noting that the rate of the Huran list member who became well established in office, with at least three terms of service, didn’t change much, constituting between 38 and 43 percent in all three terms. Also, the number of old-timers was always slightly higher in the CPPCC than in the NPC, indicating that the long term networking strategy of the rich entrepreneurs is based primarily on the consultative body. But participation in both bodies, and exchanging seats between them, is a common practice among the old-timers. In 2013 members with previous experience in the other body constituted 23 percent of the renominated, and in the last two terms that figure was 29 and 30 percent, respectively.

The data shows that almost every second rich entrepreneur in the NPC or CPPCC is a well-established old-timer with at least three terms in office. The rate is four times bigger than the one generally observed among business sectors in the CPPCC (see Figure 1), and illustrates well the networking nature of the richest entrepreneurs’ participation. Those business leaders who decide to enter national-level politics tend to stay there for longer, notwithstanding some well known cases.

This also signifies that the changes in the group of business representatives in the Xi era are not radical in terms of personal composition. The enhanced political control over the assemblies by the party leadership is most visible in the diminished numbers of participating entrepreneurs.

The question remains what is the main reason for this trend: Is it voluntary withdrawal by business leaders, caused by constrained networking possibilities, or is it rather due to conscious shaping of the participation levels by official selection, vetting, and confirmation of the candidates? Most likely it is both, since the distrust is usually mutual.