With the China-India and China-U.S. rivalries intensifying, and China’s presence and influence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) rising, the IOR is not only emerging an important site of big power competition but drawing small states in the region, such as Sri Lanka, into the vortex of these rivalries. While there is scope for cooperation among the major powers on non-traditional issues – they worked together to tackle piracy in the western Indian Ocean, for instance – the outcomes of such cooperation could be “complex,” Nilanthi Samaranayake, director of the Strategy and Policy Analysis Program at CNA, a nonprofit research organization in the Washington area, and a longtime analyst of Indian Ocean security and small states in international affairs, told The Diplomat’s South Asia editor Sudha Ramachandran.

Throwing light on the major questions in Indian Ocean security as 2023 starts, Samaranayake said that “The heightened state of strategic competition between major powers calls into question to what extent the cooperation we have seen previously may be possible in the Indian Ocean in the future.”

How has India’s naval capacity in the Indian Ocean grown in recent years?

India has made significant progress in demonstrating leadership and presence in the Indian Ocean. In particular, it has strengthened its maritime domain awareness over the past 15 years, starting with an effort to augment coastal security after the 26/11 Mumbai attacks in 2008. This investment in non-traditional security, which focused on preventing another terrorist attack, has paid dividends in the traditional security context as it expanded to partnerships in the wider Indian Ocean region.

Since then, India has steadily increased its capacity-building activities, information-sharing partnerships, and operational relationships with Indian Ocean countries. For example, India has developed a network of coastal radar stations in the island states of Maldives, Seychelles, and Mauritius. India’s Information Fusion Center–Indian Ocean Region has hosted liaison officers from roughly 10 regional countries and non-resident partners such as Japan and the United States. It has also enlarged its regional presence through the Indian Navy’s Mission-Based Deployments, which span the entire Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, the Indian Navy continues to build its fleet, most recently with the delivery of the fifth Scorpene-class submarine and the commissioning of the new aircraft carrier.

Could you share with us how Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port played a role in expanding China’s presence in the Indian Ocean?

The development of Hambantota Port has been fraught with controversy for the past 15-plus years. In addition to raising well-known questions about China and great-power rivalry, the port has been controversial domestically as well. Drivers of the port range from Sri Lanka’s maritime strategic culture and ambitions for the development of the southeast region to local politics.

Much of the port’s activity has so far consisted of vehicle transshipment from India and Japan to destinations in East Africa and the Middle East. Plans for 2023 include building the port’s fuel bunkering business, conducting repairs for transiting ships, attracting cruise liners, and pursuing development projects in the wider region.

A Chinese-majority joint venture agreed to a 99-year lease to operate Hambantota Port in 2017 when Sri Lanka badly needed foreign currency. This episode was a preview of the economic crisis that the country faces now after running out of foreign exchange reserves in 2022. The pursuit of this agreement illustrates the dilemma often confronting small states. Although Sri Lanka’s agency in making this decision should not be ignored, Chinese negotiators extracted an excessive term from a small state going through economic difficulty.

Because of the controversy over China’s role in building and financing the port and the Chinese-majority joint venture that operates it, Colombo has been deliberate about permitting military diplomacy and refueling from other countries in Hambantota. Sri Lanka has welcomed naval ship visits by the U.S., India, Russia, and Japan, as well as provided tours of the port to foreign diplomats and military officials.

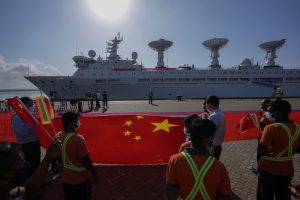

Only in August 2022, however, did the government finally permit a first-time visit by a Chinese ship, the Yuan Wang 5, to Hambantota. Not surprisingly, the lead-up to the visit reportedly generated great controversy among officials from India and China about Colombo’s wavering on whether to grant permission. This episode illustrated the pressures that small states in the Indian Ocean will increasingly face to accommodate the preferences of major powers engaged in strategic competition.

The activity of China’s maritime militia in the South China Sea is well known. Could you share with us your insights into such operations in the Indian Ocean?

Unlike in the Pacific, China has no maritime disputes in the Indian Ocean. There is concern, however, that China’s assertive activities in the South China Sea might carry over into this region. The Indian Ocean is a region where countries have historically talked about the need to maintain a “zone of peace,” going back to the Cold War.

In the contemporary era, there is increasing attention to China’s fishing activities, particularly in the western Indian Ocean. Here concern exists more broadly about illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing amid growing awareness of the depletion of yellowfin tuna stocks from overfishing.

Similarly, in the central Indian Ocean, Maldives is alarmed about foreign fishing in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the implications for the country’s food security. According to some estimates, 10,000-15,000 tons of tuna are caught illegally in Maldives’ EEZ each year by foreign vessels.

More than a decade ago, Sri Lanka’s navy arrested Chinese fishers operating without permission, but no further arrests have been reported in recent years. Fisher populations, however, have questions about China’s interest in sea cucumber farming in the northern part of the country.

Amid such concerns, monitoring EEZs is a significant challenge faced by smaller maritime forces in the Indian Ocean, given current platforms, personnel requirements, and defense budgets. They will need greater capacity to guard against unauthorized activity.

Beyond illegal fishing, another concern is dangerous military interactions between extraregional powers in the Indian Ocean. This type of incident was seen just last month in the South China Sea, when China’s aircraft flew very close to U.S. aircraft. In a separate incident back in 2018, Washington issued a protest to China for using lasers against U.S. military aircraft in Djibouti with injury to air force personnel. Such incidents have the potential to undermine regional stability.

As we start 2023, what else should we be looking at in Indian Ocean security?

We’ve been discussing traditional security rivalry, but it’s important to consider non-traditional security issues such as environmental challenges faced by the region. The COP27 headlines have passed, but climate change is viewed as an existential threat by small states in the Indian Ocean, as well as larger countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan, which was struck by catastrophic flooding last year. Developing countries were successful in securing an agreement to establish a “loss and damage” compensation fund, but the challenge remains to make progress on commitments regarding climate change mitigation.

Another issue is marine pollution from shipping accidents in Indian Ocean sea lanes. In 2020, Mauritius declared a “state of environmental emergency” after a bulk carrier ran aground and began spilling oil. In 2020-2021, Sri Lanka faced an oil tanker fire with a diesel-fuel leak and a container ship fire that emptied chemicals and debris into the ocean. It is difficult to know the long-term implications of these disasters on the marine environment, but smaller countries are concerned about the threats to local fisheries and tourism especially given high food and energy prices due to global inflation. This represents another area requiring greater cooperation going forward.

But it’s important to remember that non-traditional security cooperation can sometimes have unexpected traditional security outcomes. For example, disaster relief cooperation between the U.S., India, Japan, and Australia after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami laid the foundation for the Quad, a grouping whose “free and open” approach is contrasted with that of China. Another example lies in naval deployments from many nations roughly 15 years ago to counter piracy in the western Indian Ocean. Despite the significant decline in pirate attacks since then, the traditional security consequence is clear: China’s recurring presence in the Indian Ocean continues to this day. The heightened state of strategic competition between major powers calls into question to what extent the cooperation we have seen previously may be possible in the Indian Ocean in the future.

——

The views expressed by Nilanthi Samaranayake in this interview are personal and not the views of any organization with which she is affiliated.