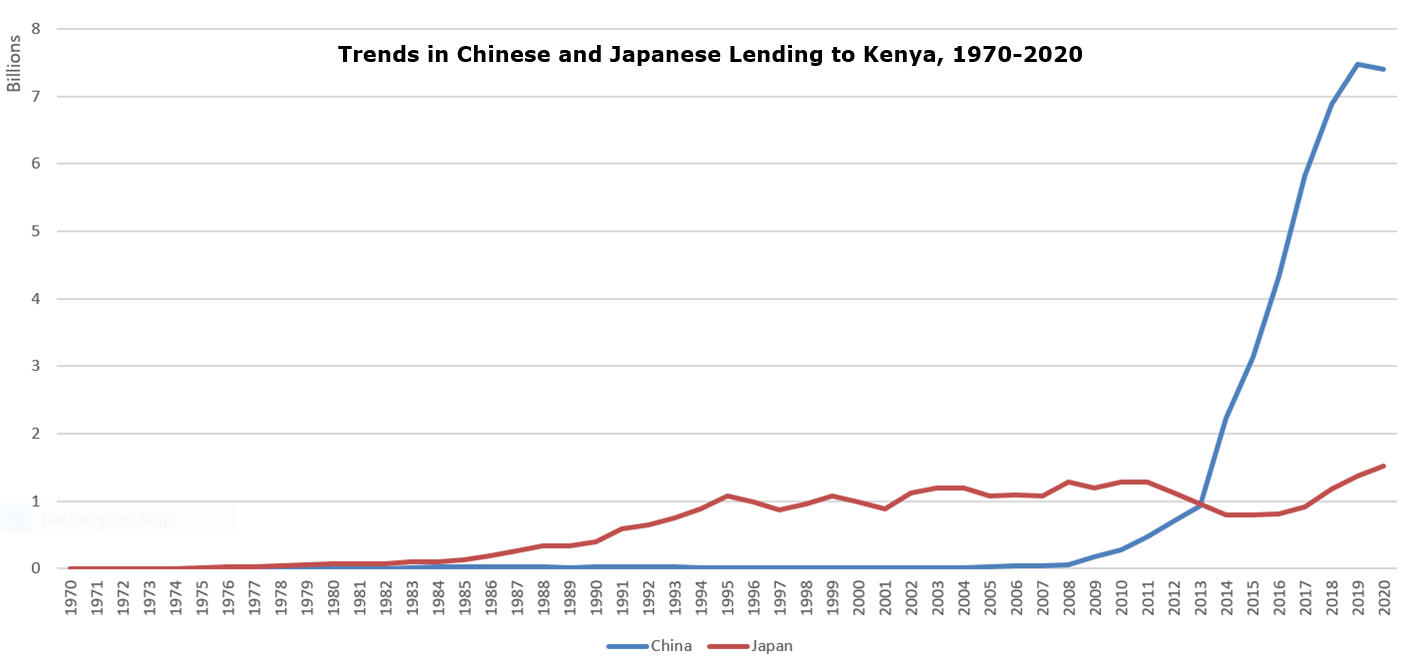

Recent media reports on Kenya’s infrastructure financing trends have suggested that Japan has overtaken China in the “loans race.” Factually, this is correct. For instance, according to The East African, fresh financial commitments from China to Kenya’s development projects fell nearly four-fold in seven years, placing China behind Japan as top bilateral lender to Kenya for the second year running. For the fiscal year 2022/23, Kenya is projected to borrow just 29.46 billion Kenyan shillings ($254.9 million) from China, a sharp cutback from the high of 140 billion shillings in Kenya’s 2015/16 budget. Meanwhile, Kenya is expected to borrow 31.11 billion shillings from Japan.

Is this a sign of things to come – perhaps a sign of China’s retreat on the African continent? Could Kenya be the first “win” for Japan and the G-7’s Build Back Better World (B3W) versus China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Africa?

History suggests otherwise.

First, Kenya’s cooperation with both Japan and China goes back decades. Kenya first established diplomatic relations with both Japan and China in 1963 after independence, and has since enjoyed warm and cordial relations with each country. Kenya has been the biggest recipient of Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) in Africa, with both grants and loans from Japan supporting a wide range of areas beyond infrastructure including agriculture, water supply and sanitation, health and medical care, education, and environmental preservation. In 2016, Kenya even hosted the 6th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD).

In contrast, relations between Kenya and China were interrupted between 1967 and 1978 due to Cold War-related geopolitics. However, the resumption of relations and a visit to China by Kenya’s then-President Daniel Arap Moi in 1980 saw Kenya and China sign two agreements. The first covered several projects such as grants for a new sports stadium (i.e. Moi Sports Center in Nairobi), technical support to two new universities (including Moi University in Eldoret), scholarships, military and cultural exchanges, and the second dealt with trade.

It was after this point that Kenya started to seek loans from China. From then on Chinese lending increased steadily, kicking into another gear in 2008 and finally overtaking Japan around 2012.

Data from World Bank International Debt Statistics

In 2012, like today, there were reports of Japan and China competing for control of East Africa’s economic landscape. This was exemplified by the advent of construction of the Thika Super-Highway by Sino Hydro Corporation, China Wu Yi, and Sheng Li Engineering Company with funding provided by the African Development Bank ($180 million), the Exim Bank of China ($100 million), and the Kenyan government ($80 million), and a 28.9 billion shilling ($340.6 million) loan by Japan to the Kenyan government for building a bypass in Mombasa.

However, given Kenya’s huge infrastructure gap, there was never really “competition.” Since 2012, the reason for China overtaking Japan in lending terms was not the number of projects but the size of the projects and what they were for.

In particular, Kenya looked to China to fund and build some of the most consequential, cross-country transport projects in Kenya – not only the Thika road but also the $480 million Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) by China Communication Construction Company (CCCC), the $210 million Southern Bypass Road, and the $3.6 billion Nairobi-Mombasa railway (the Standard Gauge Railway). Accordingly, China became a huge player in Kenya’s infrastructure space as a leading financier through China’s policy banks and a major implementor through bids by Chinese construction companies for other transport and non-transport nationally and internationally financed projects.

On the other hand, Kenya has consistently looked to the Japanese government and firms to support smaller but nevertheless crucial projects – such as building of Kenya’s geothermal power plants and suppliers of heavy duty equipment, tapping into the country’s shift to green energy. For instance, in 2017 a Mitsubishi Corp led-consortium won the tender to build 140MW Olkaria plant, a $555 million project. Other infrastructure projects include the 2006 Master Plan for Urban Transport in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area, the dualling project for Ngong Road, construction of the second container terminal at the Port of Mombasa, and the Mombasa Port Area Road Development Project.

Like China, Japan has made broad pledges to support infrastructure development in Africa. At the 6th TICAD conference held in Nairobi, for instance, Japan pledged to spend $10 billion on infrastructure projects across Africa over the coming three years, to be executed through cooperation with the African Development Bank. So none of this is new.

However, while both Japan and China provide loans, and while both also tie loans to use of their domestic firms (a practice that is seen as problematic by recipients), it should be noted that in our analysis, not only do the two countries support infrastructure projects in different sectors and sizes, but proportionally more of Japan’s grants and loans are geared toward capacity building.

So what does this mean going forward? Are we back in 2012 with roles about to be reversed, with Japan and Kenya acting as a pilot for the successful roll out of the G-7’s B3W?

Perhaps. However, the history I have outlined suggests a more uncertain future, for three reasons.

First, the future trajectory is highly dependent on Kenya’s appetite to build more infrastructure and what types of infrastructure Kenya prioritizes. Whereas in the past two financial years Japan has been lending more to Kenya versus China, China will likely remain an important player in Kenya’s transport infrastructure financing and development. In particular, China has indicated its willingness to engage in Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) for transport projects, such as the model of the Nairobi Expressway – where Kenya has partnered with China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) to construct and operate the $600 million-worth toll-road from Jomo Kenyatta International Airport to Westlands. Chinese firms may also have more interest and experience in financing industrial parks than Japan. However, if Kenya prioritizes more green energy projects or urban transformation projects, Japan’s firms will likely be the target.

Second, the future trajectory is dependent on Kenya’s appetite for bilateral concessional loans. If Kenya is able to continue borrowing, and COVID-19 restrictions in China ease, the language agreed at the most recent Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2021 suggests that Chinese banks and firms will be open to providing more loans for large projects. However, if Kenya remains under pressure by the IMF in particular to avoid taking on new sovereign debt, however cheap, Kenya’s leaders are likely to try to engage China, Japan, and other development partners in PPPs or other forms of investment financing.

Third, and linked to the above, in a scenario of constrained borrowing by Kenya, the potential for competition also depends on Chinese and Japanese firm’s openness to PPPs and investment finance as well as Kenya’s regulatory framework for these – for example, to what degree Kenya requires partnership with local firms and/or local employment. Having worked with Kenya for longer than China on smaller infrastructure projects more suitable to PPPs, Japan is better placed than China in this scenario. PPPs come with significant challenges, not least determining the optimal prices for all citizens poor and rich to have access and take advantage of their services, as well as managing citizen outreach, as is being experienced with the Nairobi expressway. Current COVID-19 protocols for international travel also put Japan at an advantage.

Overall, while the debate of China vs. Japan is interesting, history demonstrates that there is only one player that really matters, and that is Kenya. With elections in August, Kenya’s new leaders will quickly need to clarify their way forward. Publishing a China or Japan strategy, or a broad infrastructure development strategy, will help clarify intentions. The above three signals, not current statistics, will be key for Kenya’s citizens, businesses, as well as development partners to evaluate to determine whether China or Japan will feature most in the coming decades.