KABUL, AFGHANISTAN — This spring, Afghans living in various neighborhoods in the capital Kabul elected their wakilon guzar, or neighborhood representatives, casting their votes in ballot boxes or by raising their hands in gatherings in mosques. While this might be normal in other countries, it is remarkable in Afghanistan, as the new Taliban rulers have in the past consistently vilified elections as “un-Islamic.”

An Election at the Edge of Kabul

These elections stayed mostly under the radar and were barely mentioned by anyone. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for a few tweets from Taliban representatives, they might have gone by unnoticed.

One of these elections took place on March 8 in Qala-i Mir Shekar, a maze of sleepy alleyways from which the close-by barren hills at the very edge of the Afghan capital are visible. Locals, many of them from the marginalized ethnic minority of the Hazaras, were rather surprised to see a journalist visiting their area a few days after the election.

“The election happened upon the request of the people here,” a young man filling plastic bags with yogurt in his small dairy shop told The Diplomat, echoing the statements of other residents. One of them, the caretaker of one of the four mosques in the small neighborhood, elaborated that “the request for an election was already made before the fall of the [Afghan Republican] government [in August 2021], but the former government wanted bribes and the candidate did not pay, which meant that it did not happen.”

“The election itself took place in a gathering in the mosque,” one elderly man then explained. “It was all transparent and we elected our wakil by raising our hands.” This was recorded in a video obtained by The Diplomat.

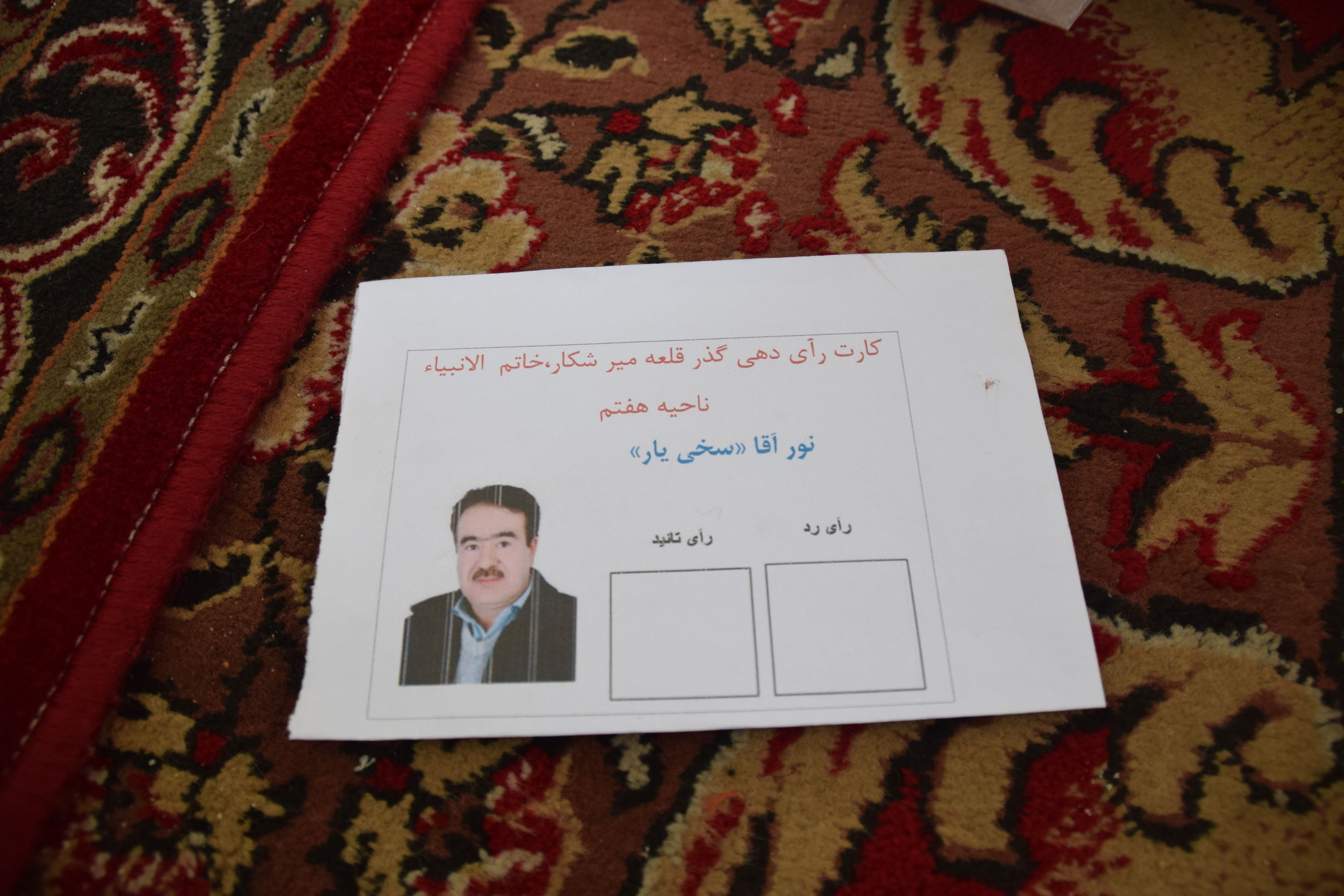

“The Taliban authorities had brought a ballot box, but as there was only one candidate and we all raised our hand in support of him, the box was not needed,” the caretaker said. That an election with ballots was planned was further confirmed by printed voting slips that were shown to The Diplomat by Noor Aqa Sakhiyar, the man who was elected as representative of Qala-i Mir Shekar.

While critics might point out that the described election was not secret and that there was no opposing candidate, for low-level local elections this is often no different in countries with strong democratic traditions. Elections of other neighborhood representatives were apparently also held with secret votes cast into ballot boxes.

In any event, the people in Qala-i Mir Shekar appeared to be happy, but also did not attach much importance to the election. Only when they were told that they might have hosted the first-ever election in the Taliban Emirate, most of them smiled, seemingly proud that their simple neighborhood had witnessed something extraordinary.

Noor Aqa Sakhiyar in the mosque in Qala-i Mir Shekar, Kabul, in which he was elected as the new neighborhood representative, March 12, 2022. Photo by Franz J. Marty.

How the Taliban Ended up Holding Elections

“As the people here asked me to become their neighborhood representative, I have since over a year tried to get elected as wakil guzar,” Sakhiyar explained to The Diplomat. “Despite my efforts, there was never an election in the times of the Republic,” he added. After the Taliban had toppled the Afghan Republic in a lightning offensive in August 2021 and returned to power, Sakhiyar waited to see what would happen.

“I then saw that the Taliban had reviewed and reissued the regulations for elections of wakilon guzar and that they only made minor changes, so I again pushed for a vote and it finally happened.”

Nematullah Barakzai, the director of publications of the Kabul Municipality, confirmed that the new Taliban administration of the Kabul Municipality had reviewed the old regulation for elections of neighborhood representatives and only made minor changes. “In essence, we added some additional requirements that candidates have to meet, such as that they have to be good Muslims and that people who had served in the intelligence service of the former government are barred,” he explained. This was confirmed by a copy of the regulation sporting a Taliban emblem that Barakzai shared with The Diplomat and in which the very few changes are highlighted.

“We just make sure that the representatives are proper and honest,” he added.

Asked about who is allowed to vote, Barakzai explained that every house in each guzar, a predefined area of around 500 houses, has one vote. Who will cast this vote is up to the household. The person just has to be over 18 years old; he explicitly confirmed that the voter can also be a woman. By mid-March, around 40 new neighborhood representatives had been elected in Kabul, Barakzai added.

Asked about why the Taliban choose to conduct elections for neighborhood representatives in Kabul after the movement had consistently vilified elections, Barakzai gave a pragmatic answer. “It is necessary that there is a liaison between the people and the administration of the [city] districts and in some neighborhoods there was no wakil guzar anymore or the one that had held the post resigned. So we had to find new representatives and it had to be someone that the people accept. The people therefore should elect their wakil guzar.”

Sakhiyar described this liaison function, which he now holds, as sharing the problems of the neighborhood with the authorities so that solutions can be found. This mostly concerns mundane but important issues, such as when to arrange the cleaning of the mostly open gutters lining Kabul’s streets.

“Every Sunday, we neighborhood representatives have a meeting with the Taliban authorities [of the city district] to discuss things,” Sakhiyar explained. “So far, there have been no problems and the Taliban are collaborating well with us.”

A ballot that was prepared for the election of a neighborhood representative in Qala-i Mir Shekar in Kabul but was eventually not used, as the election took place via a show of hands. Photo by Franz J. Marty.

Broader Implications?

Whether the Taliban decision to allow elections for neighborhood representatives in Kabul has any broader implications remains unclear.

“In the Kabul Municipality, elections are only held for wakilon guzar, but not other officials,” Barakzai explained. Asked about whether the elections in Kabul might be replicated in other towns or on a district, provincial, or even national level, he declined to comment, as this would be outside his authority. Multiple messages to two Taliban spokesmen at the national level over several weeks to clarify the issue were not answered in substance.

That said, to view these elections of neighborhood representatives in Kabul as the dawn of a democratic Taliban would be amiss. “For now, the Taliban are completely opposed to having an election-based Emirate,” Ibraheem Bahiss, a consultant working on Afghanistan for the International Crisis Group, told The Diplomat.

“As elections are such an anathema to what the Taliban stand for, they would not hold municipality-elections without purpose. In light of this, it is likely that the Taliban are employing such elections to test the utility of elections for other lower tiers of their government,” he further assessed.

Andrew Watkins, a senior expert on Afghanistan for the U.S. Institute of Peace, echoed similar thoughts. “With these low-level municipal elections, the Taliban may be gauging the reaction of the international community, testing whether such gestures will be awarded credit as more ‘inclusive governance.’ Or they may be probing their standing with urban populations, in which they have much less history of acting as authorities. They might even be gently introducing more culturally palatable forms of representative government, or at least the appearance thereof, to their own members and supporters,” he told The Diplomat.

“But to date, it is unclear to what extent this seeming experiment reflects any of those concerns,” he concluded.

Residents of the Qala-i Mir Shekar neighborhood in Kabul raising their hands in a mosque to elect their new neighborhood representative. Still from a video provided by the elected candidate, Noor Aqa Sakhiyar.

Whatever the underlying motives are, so far the elections remain an exception, or at least there have been no reports of other elections being held elsewhere. Sources in other major cities in Afghanistan asserted in March that the Taliban had unilaterally appointed neighborhood representatives and not let them be elected.

In general, one Taliban sympathizer downplayed the meaning of elections of neighborhood representatives, pointing out that they would have purely administrative tasks, but not be lawmakers. He further elaborated that the election of lawmakers would be impossible, because the law is, in the view of the Taliban, divine and cannot be amended by people.

In view of all this, the elections of neighborhood representatives in Kabul cannot be seen as an indication that the Taliban will significantly change their approach to governance, which remains, given the opaque inner workings of the movement, mostly unclear, but autocratic and totalitarian. However, the mentioned elections are a sign that in some areas that are deemed of lesser importance the Taliban might at times be open to pragmatic solutions.