In recent years, the Japanese government has attempted to upgrade its ballistic missile defense (BMD) capability to an integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) system. The deployment of Aegis Ashore to Akita and Yamaguchi prefectures was considered to be one of the integral components of Japan’s IAMD system. Then Defense Minister Taro Kono announced Japan would abandon the deployment of Aegis Ashore in June, and as a result, Japanese strategists and parliamentarians, especially the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as the largest and ruling party, resumed a debate over the option of possessing a strike capability against enemy bases. Some Japanese military analysts, especially Yoshiaki Yano, a visiting professor at Gifu Women’s University, have even contended that Japan should possess nuclear weapons in lieu of Aegis Ashore.

The policy debate over Japan’s acquisition of a strike capability against enemy bases is not a new topic. In light of the re-interpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution in relation to possession and use of a strike capability against enemy bases, the Japanese government has explained that it is not unconstitutional for Japan to possess such a strike capability for the purpose of self-defense. Indeed, an official view expressed by the Ichiro Hatoyama administration on February 29, 1956 justified the possession and use of capability to strike enemy bases, stating:

If Japan were in imminent danger of an illegal invasion, and the method of invasion were a missile attack against Japan’s national territory, I simply cannot believe that the spirit of the Constitution requires that we merely sit and wait to die. In such a case, I believe that we should take the absolute minimum measures that are unavoidably necessary to defend against such an attack, so that in defending against a missile attack, for example, if no other suitable means are available, striking the missile base should be legally acceptable and falls within the range of self-defense.

The Hatoyama government, of course, did not mention the strike capability against missile bases in relation to Japan’s BMD system. However, this official statement has been recognized as a legal basis for the acquisition of strike capability as a supplement for Japan’s limited BMD capability. In the past, whenever Japanese parliamentarians discussed possession of enemy base strike capabilities, domestic and foreign experts speculated that Japanese politicians were eyeing the military capability for a “pre-emptive strike.” This time again, the Wall Street Journal reported that Japanese policymakers have considered acquisition of pre-emptive strike capability as an alternative to the deployment of Aegis Ashore in order to deal with the North Korean nuclear and missile threats as well as the rise of Chinese military power. In addition, the Nikkei Asian Review noted that Japanese officials have explored the development of “pre-emptive strike capabilities against enemy rocket launchers as a less-costly alternative to the Aegis Ashore missile shield.”

Nevertheless, it is a total misunderstanding that Japanese officials and lawmakers have sought to acquire the military capability for pre-emptive strike in terms of its domestic legal framework. In accordance with the Peace and Security Legislation, there are several envisioned military emergency situations, such as gray-zone encounters, anticipation of an armed attack, coming under armed attack, and threats to the nation’s survival. Legally, the Japanese government is allowed to exercise the right of individual and collective self-defense if under armed attack or facing a threat to Japan’s survival. In the event of an anticipated armed attack, the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) only can stand-by for defense operations, whereas the SDF shall be dispatched for defense operations in the event of an actual armed attack or a survival-threatening situation on the basis of Article 76 of the SDF Law.

More specifically, Article 88 of the SDL Law stipulates that the use of force should be consistent with international law. A pre-emptive strike as a use of force prior to an armed attack is not explicitly permitted in international law in the first place.

Given the domestic and international legal frameworks, the Japanese government is able to possess “counterattack capability” against enemy bases for self defense. LDP lawmakers have been considering the use of that term in order to avoid domestic and international misunderstandings.

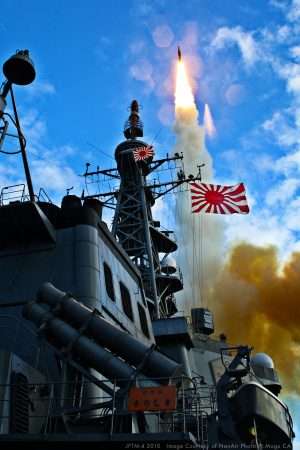

Yet, as the Asahi Shimbun noted in an editorial, it is “extremely difficult even for the U.S. and South Korean forces working together to pin down the missiles North Korea is preparing to fire.” Japan’s counterattack operations against enemy bases, moreover, shall be conducted only after armed attacks, possibly with nuclear forces, have occurred against Japan or a country that is in a close relationship with Japan. In this sense, the enhancement of Japan’s IAMD is imperative regardless of the Aegis Ashore system. The SM-3 Block 2A would be able to intercept Musudan missiles on a lofted trajectory, but is incapable of coping with surprise saturation attacks in the first place. Furthermore, the current Aegis Ashore system may not be able to shoot down Iskander-type missiles on a depressed or flattened trajectory and hypersonic glide vehicles that can penetrate existing missile defense shields on an irregular trajectory. Hence, just because the deployment plan of Aegis Ashore was withdrawn does not mean that Japan should possess a strike capability against enemy bases.

The Japanese government has already planned to acquire strike capabilities such as stand-off missiles (JSM, LRASM, and JASSM) as well as hypersonic weapons for defensive purposes. However, what Japanese strategists and LDP parliamentarians have considered is the acquisition of Tomahawk cruise missiles with a range of about 1,300 km that can target not only North Korea but also China. Strategically, it is fair to argue that if Japan possesses Tomahawk cruise missiles, both the SDF and the U.S. Forces would be able to strengthen their interoperability and joint operations in an armed attack situation or a survival threatening situation, during which Japan can exercise the right of individual or collective self-defense.

Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that Japan’s IAMD is expected to deal with possible nuclear missile attacks, and that Japan’s counterattack against enemy bases could inevitably trigger further nuclear attacks against the country. Hence, the purpose of the possession of such a defensive counterattack capability would be as a deterrent against nuclear attacks. Although possession of defensive strike capability is within the framework of the official interpretation of the Japanese Constitution, the policy debate in Japan requires cautious and sophisticated deliberations at the National Diet, widespread support and understanding of the Japanese public, and appropriate explanations for the international community to avoid increasing diplomatic tensions or security dilemmas in the Indo-Pacific region.