Cartoons are a powerful tool of political speech. Combining journalism, art, and often satire, political cartoons are all the more powerful because of their accessibility. That also makes them a threat to politicians in democracies and autocracies alike. In their new book, “Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle Against Censorship,” Cherian George, a professor of media studies at Hong Kong Baptist University’s journalism department, and cartoonist Sonny Liew illustrate (literally) the power of political cartoons by explaining the various motivations and methods of cartoon censorship across the world. In the interview below, George share insights about how censorship differs across political contexts and why cartoons are so powerful.

What is unique or special about the political cartoon medium?

Political cartoons are a cross between journalism, art, and satire. At their best, political cartoons combine the public purpose of journalism, the emotive impact of art, and the democratizing effect of satire. Of course, not all political cartoons reach these levels. As with other forms of journalism, many are mediocre. Some are toxic.

The impulse to cartoon seems universal, even if the freedom to do so isn’t. It’s such a basic and low-cost medium for commentary that you can find it everywhere. And it has a long history. So if, like me, you are interested in censorship, political cartoons are an illuminating type of journalism to study.

Governments of all stripes engage in different forms of censorship. What are some of the myriad reasons or motivations for censorship?

Well, let’s start with reasons that don’t apply to cartoons: to block exposés of corruption or state secrets. Unlike investigative reporters, political cartoonists aren’t really in the business of unearthing things that people don’t know. Instead, cartoons often crystallize what the public already knows or feels, or make people look at known facts in a new way.

What seems to irritate leaders with an authoritarian disposition is that cartoons embolden citizens. It’s like the fable of the boy who points out that the emperor has no clothes. You cannot unsee it. Confident leaders know that satire comes with the territory, and is a strength of an open society. But there are also many self-important leaders who really cannot abide being laughed at.

There is of course a quite different category of censorship, which is about protecting the dignity of various identity groups — racial, religious, gender, and so on. Under international human rights law, states actually have an obligation to prohibit expression that amounts to incitement to discrimination or violence against communities that are too weak to protect themselves in unregulated debate. We could call this “good” censorship. But although the moral and legal principles are quite clear, implementing them in a just manner is an extremely complex and controversial exercise. Around half of our book focuses on such controversies.

How does censorship differ in authoritarian, semi-authoritarian, and democratic societies?

There is problematic censorship everywhere, but the agents and methods of censorship differ depending partly on the political system. Liberal democracies have checks and balances to stop governments from censoring public discourse, so cartoonists there almost never have to worry about the state. In more authoritarian settings, governments can and do use repressive laws against cartoonists. Even more intimidating is the use of extra-legal tools by various groups, ranging from violence by paramilitaries to harassment by online mobs. In many settings, cartoonists cannot count on the rule of law to protect them from people’s outrage.

Cartoonists everywhere also contend with “market censorship.” This refers to the biases of capitalist media. The most obvious form is when news organizations refuse to publish something critical of a major advertiser or investor, or something that they fear will generate a strong consumer backlash. When editors exercise purely independent judgment, and decide that a cartoon does not meet the publication’s standards, I wouldn’t call that censorship. It’s editorial judgment. But if they go against their own better judgment because they fear the market, that’s a problem. Another kind of market censorship is when good public interest media shrink or die, leaving fewer outlets for professional cartoonists.

People who are ideologically wedded to the idea that free markets equal media freedom have a hard time accepting that “market censorship” is a thing. But it is a universal concern of political cartoonists — indeed, of all professional journalists — regardless of the political system they work within.

What role did Malaysian cartoonist Zunar play in the downfall of Najib Razak? What does his story tell us about the power of cartoons?

It takes a village to keep democracy alive, and many brave individuals and groups played a part in challenging Malaysia’s former premier, even when it seemed like he was too rich to fail. In the media sector, Sarawak Report and The Edge come to mind. Their investigative journalism helped to expose the massive corruption that was taking place.

But the struggle was never about just facts and figures, or hard evidence. UMNO was a hegemonic party, the only rulers Malaya had known since 1957. They were the natural, taken-for-granted leaders of the Malay majority. Making their ouster thinkable required years of counter-ideological work by politicians, activists, artists, humorists. Zunar contributed to this effort.

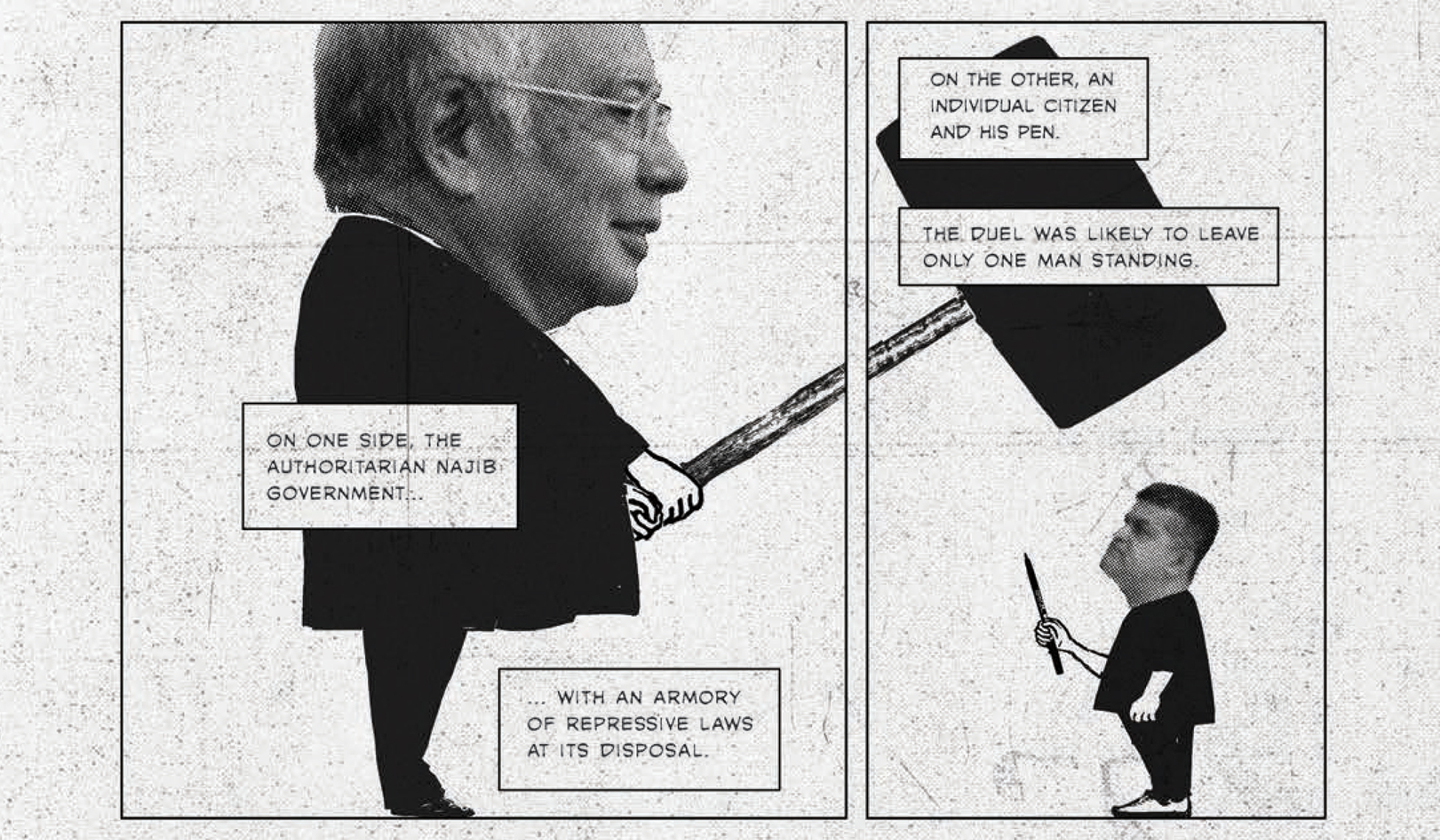

It’s not just that Zunar’s cartoons were so clever and on-point. Our book presents Zunar as a performance artist, because he is exceptionally talented in the improvisational art of making censorship backfire on his censors. There was nothing that Najib and his government did to Zunar that the cartoonist couldn’t turn into an opportunity to mock his oppressor.

I’ve seen this happen with other cartoonists as well. Often, it’s not really about the power of their cartoons. It is more about their own relative powerlessness. When the public sees these defenseless individuals stand up to the most powerful men in the land, it can be very inspiring; and when these powerful men lash out against a cartoonist, that is not a good look.

Unequal battle: Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Najib Razak versus cartoonist Zunar, as depicted in “Red Lines.” Credit: Cherian George and Sonny Liew

In discussing China, you mention political scientist Margaret Roberts as saying that “modern Chinese censorship uses a blend of fear, friction, and flooding.” Can you explain those three tactics?

We normally associate despotic media control with the use of state coercion to create a culture of fear. But researchers looking at China and other modern authoritarian regimes have found that this is not their only — or even main — form of control. Instead of attempting total bans, which are rarely watertight anyway, states can just make it harder for citizens to access the unapproved content.

The Great Firewall is the classic example. China’s walled garden is not totally impervious, but it creates enough “friction” to make it not worth the while of most citizens to look for taboo content. Another example of friction is when governments, in cahoots with internet service providers, slow down speeds during sensitive periods to make it harder to share videos. Users often can’t be sure why they are experiencing difficulties, which suits the authorities fine. Governments normally prefer their interventions to be invisible.

“Flooding,” meanwhile, involves pumping propaganda, or just irrelevant content, into cyberspace to distract from oppositional messages. This strategy suits what some call the “attention economy” — a world where the resource that is most scarce is not information as such but people’s attention. In an environment of attention scarcity, states don’t need to apply traditional censorship to manipulate public opinion. They can just drown messages they don’t like in a sea of other content.

Art is incredibly powerful, and some would argue that with such power comes responsibility. Where does the responsibility lie to not cause harm through political cartoons? What kind of restrictions are reasonable? Can this question even be answered or will cartoonists always be pushing boundaries even as societies continue to evolve?

The cartoonists I interviewed have an ethos similar to other journalists. They absolutely accept that their responsibility to society is more important than whatever ego gratifications they derive from their art. They exercise self-restraint when they think it’s necessary. It’s not as if all cartoonists have this irrepressible urge to draw the first thought that comes to mind. There are professional cartoonists who will agonize over whether an idea for a provocative cartoon crosses the line into gratuitous offense, even if they have the freedom to draw whatever they like.

There are of course always people who will disagree — sometimes violently, unfortunately — with the cartoonist’s judgment. And there are many cases where it is very, very difficult to come to a consensus. Drawings are more open to interpretation than words. This is a strength as well as a liability.