The fifth plenum of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s 19th Central Committee wrapped up in Beijing on October 29 after a four-day meeting. This year, the semi-annual gathering of China’s top leaders had a special task: finalizing the blueprint for the 14th Five-Year Plan, which will set China’s economic and social policy vision for the period from 2021-2025. The final version of the plan won’t be passed until the National People’s Congress meets in early 2021, but it is unlikely to differ in substance from this week’s blueprint.

The full text of the post-plenum communique is available here in Chinese (an English translation is likely to be released later). While it’s a dense read, full of CCP jargon, it contains essential clues about China’s trajectory over the next five – and even 15 – years.

As is typical, the communique was largely triumphalist in its tone, declaring victory in meeting the goals of the previous five-year plan. There was, however, acknowledgement of some of the problems that China still faces, including persistent (and growing) inequality between rural and urban residents, environmental issues, and – despite a heavy government focus – lack of quality innovation. The next five-year plan aims to tackle those issues.

This time, the vision for China’s economic future places a heavy emphasis on quality over raw numbers. The blueprint calls for “sustained and healthy” growth marked by “significantly improved quality and efficiency” during the next five-year period. Importantly, there is no specific target for GDP growth, something analysts have long said needs to be dropped if China truly wants to transition away from an obsession with growth at all costs. We could still see a soft GDP target added in the final version of the 14th Five-Year Plan approved next year, but for now the main focus seems to be on GDP per capita instead. The communique set the goal of raising GDP per capita to the level of a moderately developed country – a vague goal that leaves room for flexibility.

The communique also pledged to significantly reduce the earnings gaps between rural and urban residents, and reiterated a long-standing focus on “new urbanization.” Battling the rural-urban development gap has been a goal for the CCP for decades, but very much remains a work in progress.

There is also a tantalizing mention of a “breakthrough” on property rights reform. This has been something of a Holy Grail for reformists in China, long discussed but never grasped. Under China’s communist system, all land is technically owned by the government – something that especially disadvantages rural landholders, who can see their property taken away at the whim of a local government, with little compensation and less change of redress. Whether this brief mention in the communique will result in real change to China’s land rights or simply more dashed hopes remains to be seen.

As expected, the summary of the next five-year plan includes references to “dual circulation,” a new term coined by Xi Jinping last spring, amid the travails of both COVID-19’s global economic disruption and the increasingly hostile economic competition with the United States. The phrase suggests a new, inward focus for China’s economy moving forward. The “domestic cycle” (meaning internal production and consumption) will be the main focus for the next five-year plan, complemented by the “international cycle” (foreign trade and investment). The communique thus includes numerous references to the need to boost domestic demand, but no specifics on how to actually achieve that goal.

On a related note, there are some nods to increased economic opening and reform – the kind of changes foreign investors and governments always clamor for – but nothing concrete. Instead, there are general promises of “new steps in reform and opening” and the construction of a “high-standard market system” where market forces determine the allocation of resources. Given that a “decisive role” for market forces was first promised all the way back in 2013, there’s nothing here to suggest a major change on the horizon.

Most notably, there is a strong focus on technology and innovation in the communique, in keeping with the growing “tech war” between China and the United States. As Washington moves to cut off Chinese firms like Huawei from access to key Western technologies, China is pressing even more urgently to develop its own technological foundation. The communique noted that innovation occupies the “core position” in China’s modernization drive, and pointed to “self-reliance in science and technology as the strategic support for national development.”

Thus many of the long-term goals highlighted in the document are tech-oriented. China will make “major breakthroughs in key core technologies,” become a global leader in innovation, and achieve “new industrialization, informatization, urbanization, and agricultural modernization.” The “core technologies” were not named in the communique, but likely include the same technologies emphasized in other government plans: semiconductors, telecommunications, big data, and artificial intelligence.

Notably, the above technology goals are for 2035, not 2025. In addition to the normal five-year plan, the plenum also discussed a more ambitious 15-year blueprint that sets out China’s goals through 2035. According to the communique, by 2035, China should have “basically achieved” its goal of becoming a modern socialist country, although the target date for definitively achieving that goal is 2049, the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. Why the new emphasis on 2035, then? And why the longer-term horizon at this year’s plenum, rather than sticking to the typical five-year plan?

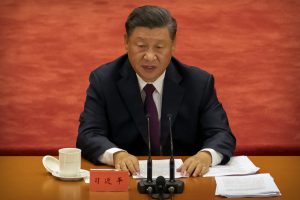

In a word: Xi. Xi has made clear that he intends on staying in power longer than the traditional 10-year term (although admittedly a young tradition). Recent precedent would have seen Xi step down as the CCP’s general secretary in 2022 and be replaced as president the next year. But no heir apparent made it onto the 19th Central Committee in 2017, setting the stage for Xi to hold the top spot in the CCP past 2022. Xi telegraphed his intention to keep power even more clearly in 2018, when the National People’s Congress amended the Chinese Constitution to remove the two-term limit on the presidency.

Now the only limit on how long Xi can hold power is one he can’t change: his age. Xi is currently 67, which means staying in power until the grand celebration of 2049 would take a miracle – he would be 96. Making it until 2035, however, is far more realistic; he would be just 82 (coincidentally, the same age at which Mao Zedong died). With an eye to securing his legacy as the man who achieved China’s modernization goals, Xi is apparently shifting the goalposts and moving the timeline forward so he can preside over the full transformation. That says a lot about his personal ambitions. It also reveals the confidence of China’s current leaders, who see their country’s rise as inevitable and unstoppable – and apparently achievable faster than previously thought possible.