In mid-January, comedian Uncle Roger apologized to Chinese netizens for hosting a video with Mike Chen of Strictly Dumpling, a China critic who had spoken out against the state’s treatment of its Uyghur minorities and the Hong Kong national security law. Also recently, YouTuber Hamji was disparaged by Chinese internet users for giving a thumbs-up to a comment that said China had wrongly claimed kimchi and ssam – both well-known Korean dishes – as their own. In another incident late last year, Chinese netizens called for a boycott of the show “Running Man” for allegedly depicting Taiwan as a separate country from China on a game board. And the list of controversies goes on.

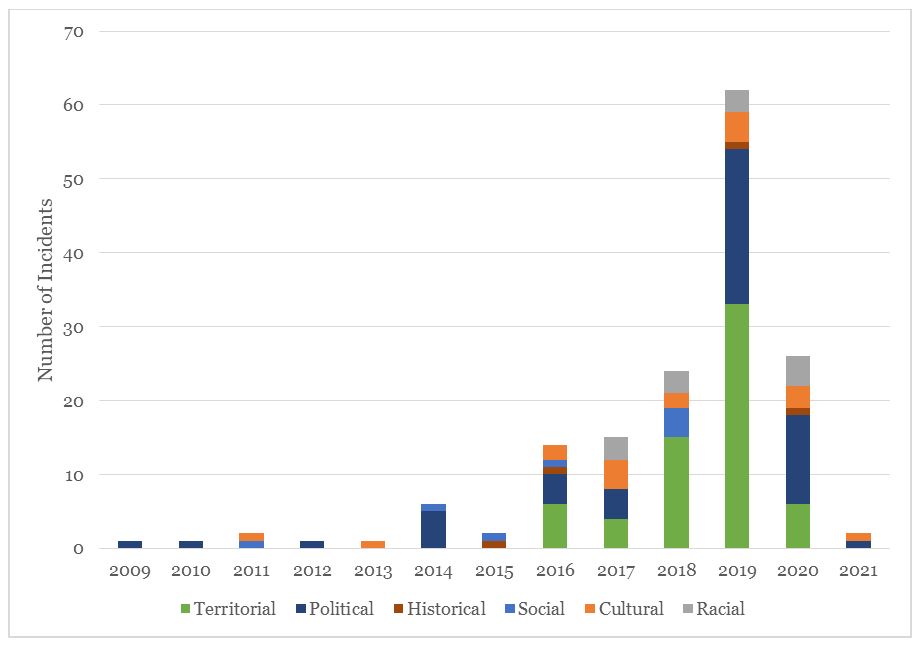

International brands seem to regularly be in the news for upsetting Chinese nationalists. Since 2014, there has been an exponential increase in such incidents. Cataloguing publicly known instances of international brands accused of offending China using open-source internet searching, data reveals 120 such incidents since 2009. There were as many as 40 in 2019 alone. Upon codification by issue area, most incidents appear to involve either political or historical issues, but cultural disputes like the one over kimchi are just as contentious.

Figure 1: Incidents of public backlash against international brands per year. Based on author’s dataset. Some events are recorded twice, as they fall into more than one category.

China’s growing international economic presence has drawn more international brands to its orbit as the latter seek to tap into Chinese markets. But as China’s foreign and domestic policy disputes have grown, so too has it become increasingly difficult for brands to stay apolitical and avoid scrutiny. Chinese netizens have made use of social media to criticize companies and celebrities who appear to misalign with the views of the state or Chinese society. The large number of incidents in 2017 coincided with the installation of the U.S. THAAD missile defense system in South Korea, and the peak in 2019 with the Hong Kong protests.

How Did China’s Digital Nationalism Come About?

The new wave of nationalism in China is predominantly based online, coinciding with the emergence of consumerist culture as affluence has risen. It takes its roots from the Patriotic Education Campaign implemented after the Tiananmen Square incident, in which Chinese youth were told of the 100 years of humiliation their ancestors were subjected to by foreign powers like the British. This has given rise to a form of nationalism that is directed toward outsiders, as nationalists seek to reclaim a sense of pride in their country.

As China has modernized, so too have Chinese citizens begun invoking their national identity in the purchase or refusal of foreign products. And this identity is not as simple as support or opposition to the party. External policy issues like that of ownership over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, or Taiwan sovereignty, make up a part of the discourse as they are perceived as regions that China has historical or political claims to – and thus rightfully belong to China.

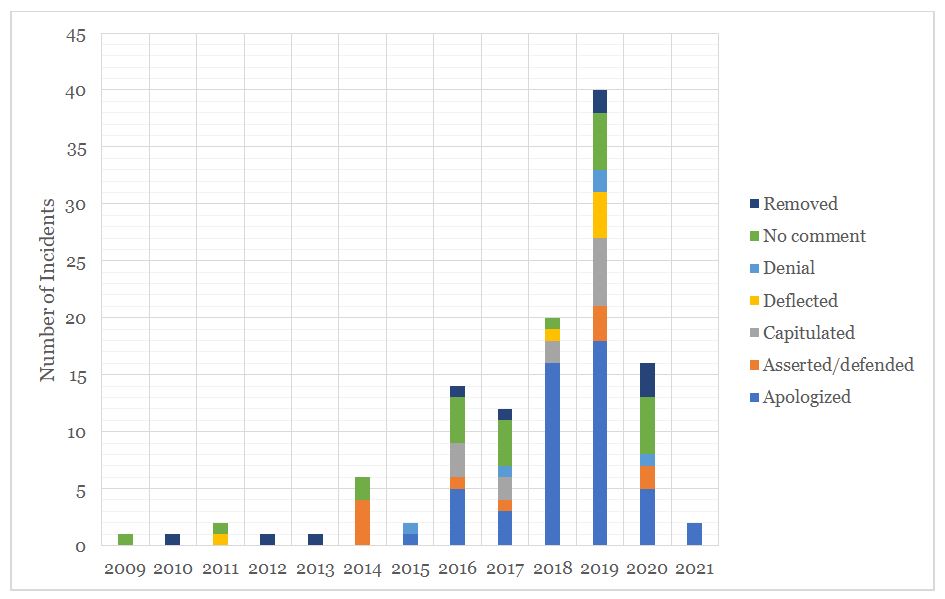

The dataset also includes information on how disputes between foreign commercial actors and Chinese nationalist netizens are resolved. Fortunately for China, most brands either apologize or capitulate because they rely on its market for profit. Some are also conscious of how quickly and violently the market can turn on them. Dolce & Gabbana’s faux pas in 2018 with an allegedly racist advertisement saw a loss of high-profile ambassadors, an expulsion from Chinese e-commerce platforms, and a storm of videos showing consumers burning their products.

Figure 2: Reactions by protest targets, broken down by year.

The party has good reason to be supportive of these nationalist backlashes as they allow China to consolidate their foreign policy positions abroad. Netizens have been praised by state media for being “engaged and passionate.” On top of this, nationalist protests toward international brands have only taken place on the internet, which reduces the security risk that a large physical mobilization might create.

Other brands who witness the fallout also conform as they do not wish to share the same fate as the brands before them. In 2018, nationalists accused several brands, including Swarovski and Valentino, of supporting independence movements when they were found to have classified regions like Hong Kong and Taiwan as separate countries; quietly, companies like Ray-ban also amended their website descriptions to avoid drawing their ire.

Controlling Nationalism: BTS and the NBA

But are there limits to the explosive nature of Chinese nationalism? Jessica Chen Weiss, an associate professor at Cornell University, has noted that, “nationalists view their activities as helping the Chinese people rather than the Chinese government.” Despite the fact that China may enjoy having their policy stances reinforced abroad, it may backfire if the anger is directed toward a brand that is deeply entrenched in society. Such was the case with the BTS and NBA controversies, in which the state had to censor the outrage festering on social media.

In October last year, BTS’ band leader RM gave a speech saying that South Korea and the United States would “always remember the history of pain… and the sacrifices of countless men and women.” Although he did not target China directly, his speech was criticized for being disrespectful to the lives of Chinese soldiers who fought with the North. But even though brands like Samsung and Fila began pulling their advertisements from social media, the Chosun Ilbo reported that the state-owned newspaper Global Times had removed articles that criticized RM, and that posts on Baidu and Weibo about the speech were taken down.

In 2019, Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey shared an image displaying a slogan that many Hong Kong protestors had chanted at their rallies, and nationalists accused Morey of supporting calls for Hong Kong independence. Morey apologized, but nevertheless, companies like Tencent began suspending their partnerships with the basketball league. Yet a few days later, police confiscated Chinese flags at the doors of an NBA preseason game in Shenzhen, and editors of state media told journalists to reduce coverage of the controversy.

Why were nationalists censored in these cases?

First, there was a high-level event that Chinese leaders did not want distractions from. Around the time the NBA controversy was taking off, Chinese officials were reportedly “ready to conclude a partial [trade] deal” with the United States. Despite nationalists taking the side of the state, the NBA controversy was actually drawing more attention to the Hong Kong protests and becoming a thorn in the government’s side. Similarly, at the time of the BTS controversy, both China and South Korea were in multilateral talks for the biggest free trade agreement in the world: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Both also wanted to use RCEP as a platform to engage in a trilateral free trade agreement with Japan.

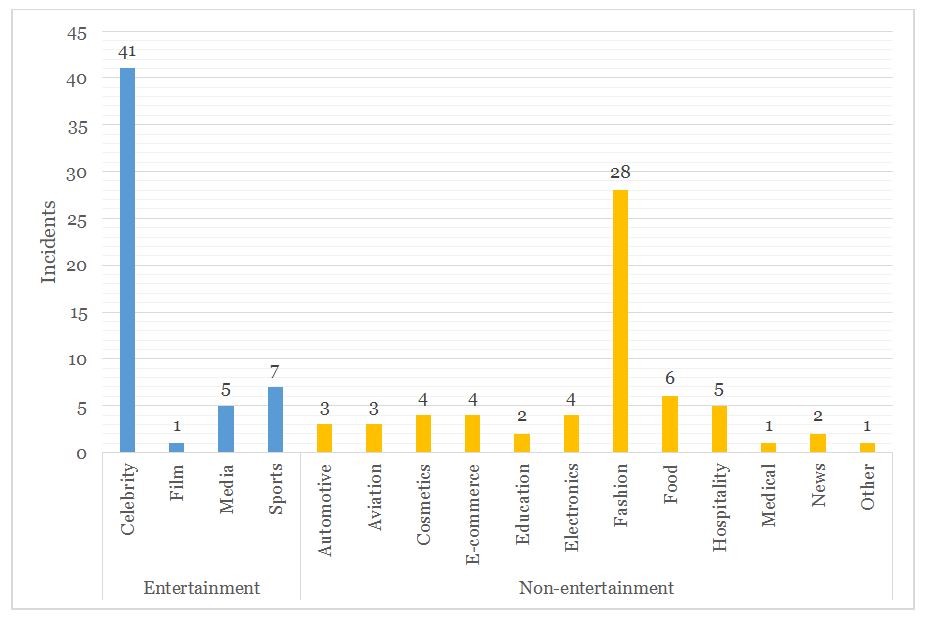

Second, the success of a nationalist protest can also be impeded by ambiguity that makes the brand more difficult to target. According to author data, 41 of the 120 incidents involved celebrities – the majority of whom apologized. This is because celebrities lack the wiggle room to blame another person for mistakes that are so evidently their own, unlike an organization, which can deflect blame on some rogue employee. For large organizations like the NBA, because figures like star player LeBron James criticized Daryl Morey’s comments, the calls for some form of retaliation toward the NBA became less unified. In the case of BTS, as RM’s comments were not explicitly directed toward China, hawkish nationalists wound up clashing with fans who had grounds to defend their idol.

Figure 3: Incidents divided into sub-industry.

Third, both BTS and the NBA wield sufficient influence in Chinese markets that a nationalist backlash would do more harm than good for China’s long-term interests. In terms of hard power, there are at least 26 international brands that work with the NBA, 14 of which are based in China like Li Ning and China Mobile. Corporations like Bank of China Group Investment have considerable investments in NBA China. Chinese firms have also invested substantially into Korean music labels, and Legend Capital for example, is a majority shareholder in BTS’ label Big Hit.

Both have substantial soft power as well. During the Cold War, the NBA was a contributing player in normalizing U.S.-China relations through the NBA-China friendship tour. NBA games are aired nationally on state-controlled broadcaster CCTV to this day, and 800 million people in China watched at least one NBA game in 2018-2019. BTS too has a considerable fanbase in China, and its growth is sponsored by a state-led campaign to expand the Korean wave. In March last year, a BTS fan club bought 220,000 copies of the group’s latest album “through a surrogate shopper” to bypass China’s embargo on South Korean commodities, a ban that was imposed after the THAAD controversy.

While the effects of cultural attraction and other forms of “soft power” are difficult to observe, it can affect domestic preferences and change how citizens want the state to engage with other actors. According to Pew, over 73 percent and 75 percent of respondents in the United States and South Korea respectively harbor a negative view of the Chinese government; if hawkish nationalists continue on their tirade, China may have an even harder time seeking cooperation from these states.

China needs to pay attention to when nationalism may hurt its interests, and might have to find alternative ways of tempering nationalist sentiment for maximum flexibility in its foreign policy. Censorship is not feasible in the long term as it could turn nationalists against the party, but ignoring it is not an option either. Just days prior to the 2016 Taiwan elections, Chou Tzuyu of the K-pop band Twice waved the Republic of China’s flag on a TV show, inevitably causing an enormous nationalist backlash. But although Tzuyu apologized, it actually led to a 3.66 percent increase in votes for Tsai Ing-wen, the current president of Taiwan who has refused to accede to the 1992 Consensus on “one China.” On the flip side, if brands want to limit the influence of the party and nationalist netizens, it would be in their best interest to strengthen their hard and soft power presence in Chinese society.

This paper owes greatly to the work of Niewenhuis of SupChina (2019), who had already compiled an extensive list of international brands who had issued apologies to China and Chinese nationalists between 2017 and 2019. I also extend my thanks to Professor Austin Strange and Sebastien Fung for their invaluable advice and guidance.