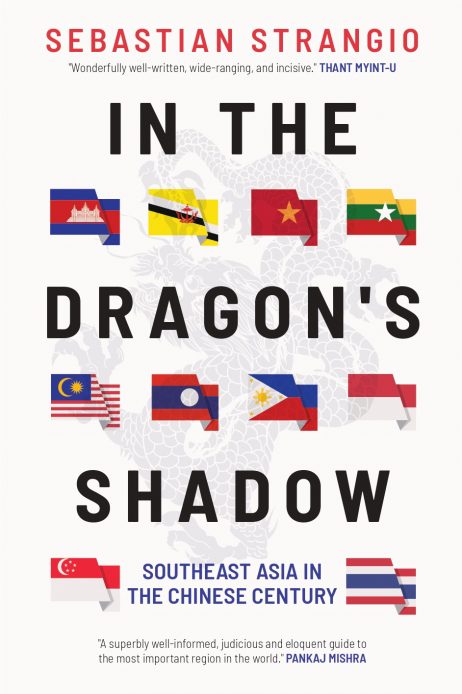

As the U.S.-China competition heats up, sparking talk of a new cold war, Southeast Asia has become a key geopolitical battleground. But as Sebastian Strangio notes in his new book, “In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese Century,” China’s presence and influence in the region is far from new – nor are the concerns China can elicit from Southeast Asia’s peoples and leaders.

Below, Strangio, The Diplomat’s Southeast Asia editor, with more than a decade of experience in the region, discusses China-Southeast Asia dynamics, the role of the United States, and how the pandemic is impacting the geopolitical calculus.

The COVID-19 situation was very much in flux when your book went to press (and frankly still is). Based on more recent developments, have you seen any indication that the pandemic will have a lasting impact on China’s reputation and interests in Southeast Asia — for better or for worse?

China has clearly suffered some reputational damage for its early bungling in Wuhan. It has also won few friends by pressing maritime claims in the South China Sea while Southeast Asian claimants were distracted by their own COVID-19 outbreaks. In relative terms to that of the United States, however, the picture has since become more complicated.

In the early stage of the outbreak, many American officials and pundits argued that the coronavirus outbreak resulted from the authoritarian nature of China’s political system. This had the unintended effect of inviting a comparison between China’s relatively effective containment of the virus thereafter, and the Trump administration’s shambolic response when the contagion inevitably reached the U.S.

The pandemic has thus hastened the erosion of the image of both superpowers, accelerating a trend that was already underway when the pandemic hit. Whether this undermines Beijing’s long-term interests in Southeast Asia remains to be seen. After all, China was hardly popular in the region before COVID-19, which has done little to dislodge Beijing’s primary advantage in Southeast Asia: its geographic proximity and economic centrality to the region. With the Southeast Asian nations now grappling with a generational economic crisis due to COVID-19, one which could soon domino into political upheavals, China looms as an unavoidable partner in the region’s recovery.

The pandemic has also been the catalyst for escalating U.S.-China competition into something more deserving of the name “Cold War.” You point out that Southeast Asian approaches to China are “anguished and complex”; how can this complexity survive in an increasingly bipolar Asia?

I don’t think that the region faces a truly binary choice — at least not yet. The original Cold War involved two superpower blocs, each proffering their own universalizing ideology, locked in a struggle that left few regions of the globe untouched. In Southeast Asia, this involved Chinese and Soviet attempts to foment communist takeovers through armed struggle. For many of the region’s governments, the Cold War thus had existential stakes.

Today’s situation is more muddled. China and Southeast Asia are deeply entwined economically; they also share other important common interests. For all its meddling, China is not seeking to export any particular ideology to the region. While the idea of economic “decoupling” is all the rage in Washington, this is not something that the Southeast Asian nations could easily accomplish, even if they wished to. For instance, Vietnam has long sought to reduce its economic reliance on China, but has found this to be much easier said than done, given the importance of sustained economic growth to the legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party. Even among “like-minded” powers like the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia, there remain important differences of opinion about how best to meet the China challenge.

Today’s Southeast Asia is in many ways a naturally multipolar region, where the interests of numerous outside powers overlap. In addition to the U.S. and China, these include India, rising slowly to the region’s west, and Japan, which has been the main beneficiary of the loss of trust in the U.S. and China. Other important players include Australia, South Korea, Russia, and Taiwan. This multiplicity of interests offers the Southeast Asian nations vital space for maneuver. The region has become an arena for U.S.-China competition, but is not yet wholly defined by it.

You note that “the very thing that enables ASEAN to reconcile clashing sovereignties — its flexible, consensus-based form of decision-making — now threatens to paralyze it.” With the regional states’ approaches to China varying so greatly, what role does ASEAN still play in shaping Southeast Asia’s foreign policy agenda?

You note that “the very thing that enables ASEAN to reconcile clashing sovereignties — its flexible, consensus-based form of decision-making — now threatens to paralyze it.” With the regional states’ approaches to China varying so greatly, what role does ASEAN still play in shaping Southeast Asia’s foreign policy agenda?

During the Cold War, ASEAN enabled the nations of Southeast Asia to retain some measure of autonomy in the midst of a great power competition that ended up ravaging large parts of the region. That ASEAN succeeded where previous attempts at Southeast Asian regionalism failed was no foregone conclusion. Today, it is easy to forget the rancorous disputes that marked the early postcolonial period. Two examples: Konfrontasi, the low-level war that Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, waged against the new Federation of Malaysia after 1963; and the spat between Malaysia and the Philippines over the region of Sabah in northeastern Borneo. To a large extent, ASEAN has softened these intra-regional disputes, and prevented a region once termed “the Balkans of Asia” from going the way of its European counterpart.

The price of bridging the divergent interests was to base ASEAN on the principles of sovereignty and consensus-based decision making. Since the end of the Cold War, ASEAN’s absorption of new members has necessarily diluted its shared interests, opening up spaces into which Beijing has thrust wedges of economic inducement. Even in the best case scenario, ASEAN will never dictate terms to the great powers. But as in the past, the benefits of standing together, even on a threadbare consensus, far outweigh those of going it alone. ASEAN has many shortcomings: some of these are structural, and some can be put down to failures of vision and leadership at the national level. But the region would be much worse off without it.

As you explain in the book, there is a contradiction between Beijing’s self-image (China as a victim of imperial powers) and perception in the region of China as an imperial power — or at least possessing that potential. Amid growing accusations of “neocolonialism” and “debt traps,” do you see any sign that China is adjusting its approach to Southeast Asia in acknowledgement of these concerns?

There are some indications that the Chinese government is aware of its reputational deficit in Southeast Asia. At the Second Belt and Road Forum in April 2019, Xi Jinping promised to address concerns about environmental issues related to Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, and announced the creation of a debt sustainability framework in order to counter charges of “debt trap diplomacy.” Whether these efforts will succeed is another question. As I see it, China faces two primary challenges. The first is the vestige of imperial hauteur that has accompanied its reemergence as a great power. Again and again, Chinese officials have shown a tin-ear for criticism – even to the idea that Chinese activities or behavior could arouse such criticism in the first place. This makes effective public diplomacy difficult.

The second problem is the sheer multiplicity of China’s engagements with the region. In practice, much Chinese activity exists outside the effective control of the central state, or in tension with Beijing’s broader interests. A good example is the rash of casino developments that have sprung across mainland Southeast Asia, from Sihanoukville in Cambodia to the rebel zones of eastern Myanmar. In just about every way, these are counterproductive to Beijing’s goals in the region: they involve the laundering of capital flows from China, and have elicited overwhelmingly negative reactions from locals. In some cases, casino concessionaires have even adopted the branding of the BRI, tarnishing its reputation into the bargain. In many ways, this challenge represents an outgrowth of the governance challenges that pertain within China itself.

When we talk about China’s influence in Southeast Asia, what we often mean is China’s influence among political elites (for example, Hun Sen and his government in Cambodia or the Duterte administration in the Philippines). Where do you see the biggest schisms between elite and public perceptions of China? Should Beijing be worried about such gaps?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has always struggled to project an appealing image to the world. “Soft power” cannot be created by party diktat. The U.S. has excelled in its ability to produce and absorb a cultural and political self-critique, something that is anathema to the CCP. The result is that China has a perpetual image problem in Southeast Asia, on top of the concerns stirred up by its behavior in the region. In terms of public opinion, the greatest gap between public and elite perceptions exists in Vietnam, where anti-Chinese sentiment cuts across every social and political divide. There is also a yawning gulf in the Philippines, where the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte in many ways represents an exception to the nation’s U.S.-friendly norm.

Beijing certainly has reason to be worried about its poor public image. Negative public opinion heightens the risk of sudden reversals, as we saw in Myanmar in 2011 and 2012, when the country’s political opening was accompanied by a sudden reversal of Chinese influence. However, the effect of public opinion on state behavior is unclear. First, there is the question of whether democratic institutions and mechanisms exist that can translate public opinion into public policy (sadly, in Southeast Asia this can’t be taken for granted). Second, the structural factors underlying nations’ relations with China ensure a considerable degree of continuity. Any government that comes to power in Jakarta or Bangkok will sooner or later be confronted with the challenge of China’s proximity, and the need to balance public concerns against the maintenance of a beneficial economic relationship.

Again, Myanmar demonstrates the quandary well. Despite pushing back against Chinese influence and opening relations with the West, the country’s government soon found itself on the defensive on a number of human rights crises, including its horrific assault against the Rohingya in northern Rakhine State. This served to alienate Naypyidaw from the West – and so the pendulum began swinging back.