The breadth of Russia’s propaganda machine hardly needs detailing. Between Sputnik and RT, formerly Russia Today, the Kremlin’s ability to broadcast its slant – to weaponize information, as the phrase goes – has been well covered over the past year. The reverberations have been easy to see, with Congressional hearings and NATO both dedicating time and energy to the phenomenon.

But with the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on the Kremlin’s disinformation campaign, one question remains: Has it worked? Has all this effort – all this time spent muddying the narratives and misleading the audiences, all for the sake of furthering Russia goals in the former Soviet sphere and beyond – panned out?

Perhaps it’s too early to tell. But according to at least one metric, it appears that Russia’s attempts at painting itself in the developed world as a bulwark against the West, as a force against liberalism, has not found very much success at all.

A new global poll from Gallup found that Russia “earned the lowest approval ratings globally for the eighth consecutive year and posted the highest disapproval ratings it has received to date.” Only 22 percent of those surveyed approved of the “job performance of the leadership” of Russia. That compares to 45 percent approval for the U.S., 39 percent approval for the EU, and 29 percent approval of China.

Russia’s bleak numbers fit within a recent line of polling that regularly shows Moscow as one of the most disfavored, most isolated nations extant. Between the Crimean occupation, the self-sanctions, and the continued invasion of eastern Ukraine over the past year, trends have only accelerated – with the huge sums Moscow has expended on propaganda outlets apparently holding little sway. Even Afghanistan, one of the few nations to acknowledge the Crimean annexation, has seen its approval of Russian leadership drop 13 percent in just the past year.

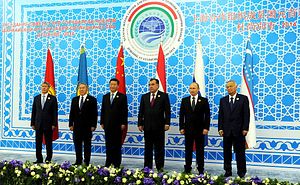

That said, if there’s an audience for whom such media appears to have worked, it is both domestically and within Central Asia. According to the figures, Russian disapproval of U.S. and EU leadership has nearly doubled over the past year, to the highest disapproval rates of any nation surveyed. Likewise, according to Gallup, “Russians’ approval of China’s leadership jumped to a record 42%.” Central Asian states also fell largely within Russia’s line. As the report notes, “Kazakhstan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan all reported the highest disapproval ratings for the U.S., the EU and Germany in 2014 than at any previous point in the past that Gallup has measured.” Kazakhstan actually tied with Ethiopia for the steepest drop in U.S. leadership approval ratings, plummeting 28 percent in just a year – with only 9 percent approving of Washington’s leadership. Tajikistan, meanwhile, saw the third-biggest drop, slumping 20 percent to come in at 25 percent total. Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan likewise posted three of the four highest approval ratings for Moscow, coming in at 93 percent, 79 percent, and 72 percent, respectively.

The usual caveats about the difficulties of polling in the former Soviet Union should apply here – all the more on a subject as charged as approving of Moscow’s leadership both near and abroad. And it’s worth keeping in mind that this polling took place before Central Asia began feeling the bite of Russia’s recession, which is just starting to hit. But still, the trends are clear: further split between Moscow and the West, further willingness of these three Central Asian states to toe Moscow’s line, and further benefit sliding China’s way. RT and Sputnik may have failed to flip these trends in the West, but their narratives have seemingly burrowed throughout Central Asia.

As The Hague Center for Strategic Studies recently wrote, “RT and Sputnik risk undermining fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, human rights, and democracy within nations that lie within the Russian orbit, as alternative sounds are crowded out.” Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan fall square into this assessment, some of the few nations for whom the Russian narrative over the past year has found a home.