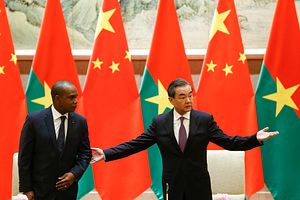

On January 4, 2019, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Burkina Faso, one of Beijing’s newest allies snatched from Taiwan, and pledged 300 million Chinese renminbi ($44 million) in support to the regional G5 Sahel force. But China’s latest catch in Africa is more than about checkbook diplomacy; it is about peer pressure and domestic politics underlined by security concerns.

In May 2018, Taiwan lost one of its last allies in Africa, when Burkina Faso switched its recognition in favor of China, leaving Taiwan with only eSwatini (Swaziland) as a partner on the continent, and 18 state-to-state diplomatic relations globally (now down to 17). Scholars and pundits have so far explained Burkina Faso’s move chiefly through China’s checkbook diplomacy, considered the core of its strategy to isolate Taiwan. While this is a significant explanatory factor, this approach fails to underline the importance of domestic and regional dynamics, especially in light of growing security concerns posed by terrorism within the country and in its vicinity. This set of factors helps us understand the timing of Burkina’s latest allegiance shift.

On May 24, 2018, the Burkinabè government of President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, elected in 2015 – a year after a popular insurrection toppled former President Blaise Compaoré – announced they were breaking off diplomatic ties with Taiwan. Two days later, Alpha Barry, minister of foreign affairs, traveled to Beijing and signed the resumption of diplomatic relations between Burkina Faso and China. In July 2018, Chinese Vice Premier Hu Chunhua opened the new Chinese embassy in Ouagadougou.

While this shift came as a surprise, it was not the first time Burkina Faso changed gear in its choice of partner. Over the last half century, Burkina Faso’s relationship with Beijing and Taipei has indeed been characterized by “yo-yo diplomacy” marked by frequent shifts. In the early 1960s, shortly after achieving independence, Upper Volta, as Burkina Faso was known then, first established ties with Taiwan. This was in accordance with President Maurice Yameogo’s dislike of China’s communist ideology and what he considered Chinese subversion in Africa. In the early 1970s, under the presidency of Aboubakar Sangoulé Lamizana, Burkina Faso was hit by a famine and measles epidemic; China’s Prime Minister Zhou Enlai rushed to offer healthcare assistance, which was repaid with a switch in recognition from Taiwan to China. For nearly two decades, from 1973 to 1994, China maintained its newly acquired ally with generous aid packages, particularly in the agricultural and medical sectors.

Despite good bilateral relations, in February 1994, Burkina Faso’s president Compaoré, in power since 1987, surprisingly cut ties with Beijing and turned to Taiwan once again. At the time, Burkina Faso was faced with a monetary devaluation crisis and the imposition of structural adjustment programs by the IMF and was therefore looking for alternative sources of support. Archives allege that Taiwan incentivized the move by paying between $50-60 million to Burkina Faso in 1994 in exchange for recognition.

This short historical narrative shows how countries like Burkina Faso often played on the China-Taiwan competition to serve their own self-interest, and were more susceptible to do so in the wake of a domestic crisis and political transfers of power. Meanwhile both Taiwan and China have used checkbook diplomacy to buy their diplomatic ties and recognition in Africa since the end of colonialism.

Despite this rocky history, the abrupt decision to ditch Taiwan in May 2018 came as a surprise, especially because the previous year, the same Burkinabè government rejected a $50 billion incentive from China to do so. At that time, Foreign Minister Alpha Barry described China’s action as “outrageous proposals” while reinforcing that “Taiwan is our friend and our partner. We’re happy and we see no reason to reconsider the relationship.” This declaration was made on the backdrop of a new deal between Burkina and Taiwan sealed in September 2016, when Burkina secured $47 million worth of subsidies spread over two years for sectors like education, agriculture, and defense. But when later that year Burkina Faso sought a further $23 million to fund five new projects, President Tsai Ing-wen of Taiwan refused to bear the cost. China, on the other hand, appeared willing to help, and promised to build a new hospital worth 122,000 euros ($136,000) in Bobo Dioulasso, the country’s second largest city, and to take over all ongoing Taiwan-funded projects. China’s checkbook diplomacy therefore appears to have won Burkina Faso over for a second and probably final time

However, while financial incentives certainly played a part, another set of factors have been largely unaccounted for in the current media and scholarly literature available, which helps explain the timing of the change from Taiwan to China: Burkina had been facing growing peer pressure from its neighbors in the context of regional cooperation and increasing security threats.

Indeed, armed groups have been proliferating across the Sahel region for many years, from Northern Mali, which was occupied by Tuareg independentists and Islamist groups in 2012, to the Lake Chad region, which has been targeted by the Boko Haram insurgency since 2009. For a while, Burkina Faso had been spared, but the fall of Compaoré’s regime was followed by attacks from various terrorist groups based in Mali, Niger, and now in northern Burkina Faso. The capital suffered three large-scale attacks in January 2015, August 2017, and March 2018, while smaller but more frequent operations have increasingly rocked the northern and eastern regions of the country.

Considering growing regional insecurity, the governments of five Sahelian countries – Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger – decided to pull their forces together through the set up of the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Launched in July 2017, the organization brings together 5,000 troops aimed at responding to growing armed group activity around their common borders in the Sahel region. The G5 Sahel is endorsed by the African Union and recognized by the UN Security Council, but it lacks the necessary funds, tactical training, and domestic reforms to operate efficiently. It is mainly sponsored by France, which already has an established presence in the region through the ongoing Barkhane operation and it remains dependent on its ability to rally support from international partners to attract more support. For example, the United States has been reluctant to deploy American troops for combat purposes, restricting itself “to advise, assist, and train African militaries.” As the United States has been looking to cut down its contribution to the UN, it has also been refusing to authorize the force to receive direct funding from the UN under the claim that it “will make the force even more dependent on individual pledges and donations.” Instead, only under pressure from France and the death of American soldiers in Niger, did the United States agree to contribute $60 million.

China, on the other hand, was willing to fund the G5 but Burkina’s ties with Taiwan were raised as an obstacle. According to Alpha Barry, during the round-table in Brussels in February 2018, the People’s Republic of China delegate made it clear that “[Beijing] cannot fund the G5 Sahel because of Burkina’s presence. It created an uncomfortable situation both for us and our neighbors.” Thus, China opted to support directly, in a bilateral fashion, each of the four other member states with which they have diplomatic relations. Burkina’s allegiance to Taiwan stood out as the only impediment from achieving the otherwise much-needed financial support, not only for itself, but for the G5 Sahel force and the region as a whole.

In conclusion, the complex picture of “yo-yo diplomacy” between Burkina Faso, on the one hand, and Taiwan and China, on the other, cannot be explained only in light of checkbook diplomacy and domestic transfers of power without taking into account the security challenges and regional pressures currently affecting the country. While this move clearly diminishes Taiwan’s international support, it also has the potential of changing the landscape of the African continent. China continues to promote a “no strings attached” partnerships with minimum safeguarding against potential abuse of human rights, which is worrying for protection and security outcomes. Meanwhile, China’s renewed ties with Burkina Faso also consolidate its position in Africa at the expense of other Western countries, primarily raising China as a strong economic competitor to France’s “chasse-gardée” in Burkina Faso. All these implications are likely to trigger a complex ripple effect on great power relations and their influence in Africa.

Dr. Oana Burcu is Assistant Professor in Contemporary Chinese Studies at the School of Politics and International Relations and Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at University of Nottingham, UK.

Eloïse Bertrand is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Warwick, working on the role of opposition parties in Burkina Faso and Uganda, and a research consultant on sociopolitical issues in West Africa. She is based in Ouagadougou. She tweets at @Eloise_Btd.