The trend in China-India ties is a predictable affair at present: Bilateral antagonism is taking the lead over any pretense of engagement and stability. Recent years increasingly suggest that.

On December 9, the Indian and Chinese military forces clashed along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Yangtse area of the Tawang sector in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. The conflict resulted in injuries (but not fatalities). This is one of the major incidents in the more than two years after the defining China-India clash at Galwan in the Ladakh region. In 2021, although there were reports of a minor face-off between Indian and Chinese patrol parties in the eastern sector, it did not result in injuries and the matter was resolved at the local military commanders’ level. Before the clashes of 2021, the previous such incident in this sector had been in 2016.

It is highly likely that the high-altitude joint exercises (“Yudhabhyas,” literally meaning war practice) conducted between U.S. and Indian troops in northern India’s Uttarakhand state days before was a catalyst for the December border incident. China’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs criticized the exercises as a violation of bilateral agreements and not conducive to building trust.

Nonetheless, instances of Indian Army patrols clashing with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops are not out of the ordinary due to the differing perceptions of the LAC between the two countries: There is no delineation of the de facto border, nor any agreement on the sharing of maps (about 20 years ago, there was an initial exchange of maps on the Middle Sector, where the dispute is relatively minor). Moreover, China’s projection of a flexible LAC plays to its expansionist tendencies, enabling it to continually engage in so-called “salami tactics.”

How far will the latest fracas impact India-China ties in 2023? Is tension in border areas becoming a “new normal”? Can a temporary political, if not a permanent, solution emerge in 2023?

Legitimizing Its Eastern Theater Assertions

Recent trends highlight that Arunachal Pradesh – over which China lays historical claims, calling it “Zangnan” or South Tibet – has become the “new focal point of confrontation” in India-China border tensions. For a long time, China has routinely protested the visits of top Indian leaders or officials to the state and has not been issuing visas to Arunachal officials while providing stapled visas to its residents. In 2017 and then again in 2021, China “standardized” the names of six and 15 places, respectively, (including residential areas, mountains, passes, and rivers) in the Indian state as part of its strategy to lend legal credence to its territorial claims.

Months before the second round of “renaming,” China had passed the Land Borders Law, which came into effect in early 2022, to strengthen its legitimization of unilateral land claims on disputed territories. This law, which upped pressure on India, must be viewed in the context of Xi Jinping’s overall security-obsessed major power diplomacy and aggressive military maneuvers throughout the Indo-Pacific. It is poised to be a major coercive tool in the near future against China’s land neighbors, especially India.

Moreover, in 2021, China also enacted another contentious law, namely the Coast Guard Law, and revised its Maritime Traffic Safety Law. Such actions have put neighbors like Japan on red alert due to China’s intent to unilaterally change the paradigms of international maritime law (e.g., through its navigation restrictions) so as to pursue unabated territorial expansion. For India, especially in the Indian Ocean, China’s maritime legal structure spells trouble.

Arguably, following the Galwan conflict, it was only a matter of time before China extended its aggressive tactics to other areas of dispute along the LAC. On this note, it can be assessed that conflict in Tawang was inevitable, especially as it is the historical, cultural, and political “flashpoint” of the Tibet question. Furthermore, the region figures centrally in Xi’s quest for Chinese “rejuvenation” and “revitalization.” The new law and intermittent clashes at the border are only further evidence that India is being dragged into protracted turmoil.

India for its part has been quick to comment on preparing for “unsettling” changes due to China’s hegemonic rise as a superpower. It has also been diplomatically assertive about not giving into China’s calls for a fractured bonhomie (i.e., tensions at the border but a facade of normalcy elsewhere). The latest incident in the eastern sector belies official Chinese assertions of “stable relations” and reaffirms the Indian side’s continued stress on “abnormality” along the border. So even as disengagement at key locations in the western Himalayas after 16 rounds of negotiations furthered a temporary thaw in ties, the clash in the eastern sector raised the hackles and undid the impact of the limited rapprochement elsewhere. A similar trend should be expected in 2023.

Anticipating the Coming Year

Unsurprisingly, in the wake of the December Tawang clash, the recent 17th round of the India- China Corps Commander Level talks over Galwan disengagement resulted in no breakthrough. The presence of sizable PLA forces along the border highlights that unless disengagement is followed up with de-escalation, the bilateral relationship remains fragile. The fear or prospect of small incidents snowballing into an uncontrollable crisis is not preposterous.

Earlier in October, Xi’s re-coronation for a third term and consolidation of “personalistic rule” at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sealed the mistrust between the two sides for the near future. This is largely because of the increase in frequency and intensity of border conflicts in tandem with psychological tactics to maintain an upper hand in the battle for bilateral and regional supremacy during Xi’s previous two terms.

With the 20th Party Congress, Xi is assured of the absolute loyalty of the Central Military Commission (CMC) – the CCP regime’s top military decision-making body, which controls and guides the PLA. For India, this implies that border escalations will continue in the same pattern as before (i.e., military maneuvers to fight and win “local wars” along with the banal rhetoric of “win-win” cooperation), if not become more fraught due to unintentional (or intentional) missteps.

Moreover, the India-U.S. growing strategic partnership, India’s participation in Indo-Pacific forums like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), and India’s growing defense cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners have not only instigated China in the recent past but also contributed to the already low level of mistrust. Ironically, India’s actions are a direct result of the constant and long-term China threat.

In the coming year, China will be watchful of India’s diplomatic and foreign policy strategy toward Indo-Pacific partners like Australia, Japan, the European Union (EU), and the United States. For example, with Japan’s new security strategy shedding its post-World War II pacifism, hardening its stance against China, and looking to collaborate with “like-minded” partners such as India to stave off the China threat, New Delhi’s response and participation in such evolving tie-ups will undoubtedly impact Sino-Indian ties.

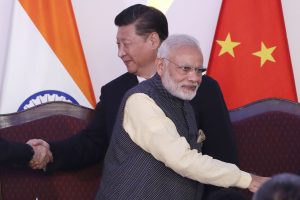

On the bilateral front, political interactions between India and China have been low profile since 2020. After a long gap, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Xi met at the Group of 20 (G-20) summit in Bali in November 2022, where the two had a brief uneventful exchange, without even the promise of a formal bilateral meeting. At the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in September, the two did not meet personally despite disengagement along the border, highlighting the soured relations.

In 2023, too, Modi-Xi interactions will likely only take place at the multilateral level. India’s presidencies at the G-20 and the SCO will not allow for a total breakdown in ties. However, bilateral political meetings will be a low-key affair due to the active mistrust between the two sides and India’s assertive diplomatic stance against China.

In 2022, India’s and China’s superficial (unwitting) alignment with Russia, as well as China’s outreach to India due to New Delhi’s growing strategic importance for the West amid the Ukraine war, allowed for a simmering down in India-China tensions. Although the latter half of the year seemed to suggest a divergence in India-Russia ties, the frigid reality at the border ensures that India will continue to strengthen ties with Russia in part to offset China’s aim of taking advantage of Russia’s international isolation. Thus, 2023 will again witness deft and ambitious global diplomatic maneuvering on both sides to press for any leverage in the one-upmanship game.

Overall, the coming year will witness no drastic improvement in China-India ties even though there might be occasional political overtures to reshape it and maintain a level of continuity of minimum engagement.