The recent round of tensions between China and Indonesia in the Natunas, which comes as Beijing and Jakarta commemorate the 70th anniversary of their ties in 2020, has once again put the spotlight on the flashpoint, and that is expected to continue with a range of ongoing Indonesian reactions. But more broadly, it is also just the latest in a series of reminders over the past few years that Indonesia’s current approach to the South China Sea has not proven successful in deterring Beijing’s incursion into Jakarta’s waters. Understanding why that is the case, and when and how that could change is important not only for Indonesia, but other Southeast Asian countries as well.

While deterrence is a term that is thrown around quite frequently in an informal manner, in the academic literature drawing from experts such as Thomas Schelling and Glenn Snyder, it tends to be viewed as one form of coercive diplomacy that seeks to prevent an actor from seeking new gains (as distinguished where possible from compellence, which would mean requiring an actor to give up previous gains). And though these options are spotlighted quite frequently, it is important to keep in mind that these are only two choices on the full spectrum of strategic interaction between cooperation and conflict, with others including engagement and accommodation.

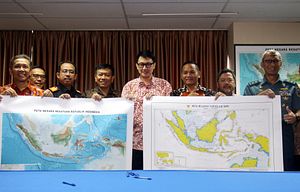

While Indonesia technically does not consider itself a claimant in the South China Sea disputes, it is an interested party. For one thing, China’s nine-dash line overlaps with the exclusive economic zone around the resource-rich Natuna Islands. More broadly, Jakarta also looking to preserve its foreign policy autonomy, safeguard regional stability, and uphold international law, including the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), as the world’s largest archipelagic state. And as I’ve detailed here and elsewhere, Indonesia’s traditional approach to the South China Sea since the 1990s might be best summed up as a “delicate equilibrium” – seeking to both engage China diplomatically on the issue and enmeshing Beijing and other actors within regional institutions (a softer edge of its approach, if you will) while at the same time pursuing a range of security, legal, and economic measures designed to protect its own interests (a harder edge).

China’s growing assertiveness over the past few years has challenged Indonesia’s traditional approach, including through multiple incursions into Indonesian waters. And while the administration of Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has taken actions in response to periodic incursions, including shoring up military capabilities related to the Natunas and launching diplomatic protests, there has been no fundamental departure from Indonesia’s traditional approach and Chinese incursions have continued episodically. It should be emphasized here that Indonesia is not alone in this challenge – China’s deliberate efforts at cyclical incursions and escalations to test responses have also posed a huge issue for South China SEa claimant states, be it Malaysia, which traditionally prided itself on having a special relationship with Beijing, or Vietnam, which remains the most capable of standing up to China.

Seen from that perspective, the latest episode is a reminder that Indonesia’s current approach to the South China Sea has not proven successful in deterring Beijing’s incursion into Jakarta’s waters. China’s incursion illustrates that little about its behavior has changed. And while Indonesia has taken a series of actions to respond to the latest episode, including maintaining a steadfast position in its rhetoric, visits to Natuna by top officials including Jokowi, and shoring up its military capabilities to a significant extent, the general contours of the response are nonetheless along the lines of what we have seen up to this point as well, in a year where the South China Sea could heat up as a flashpoint more generally.

Looking ahead, even if Indonesia does not depart fully from its overall Southeast Asian approach, there are steps that Indonesia can take to shore up deterrence against future Chinese actions. Conceptually, the deterrence literature building on Schelling and others distinguishes between deterrence by denial and deterrence by punishment. If Jakarta intends to respond via deterrence by denial, it can work to reduce the likelihood of future Chinese incursions occurring by building up its military capabilities, reinforcing its alignments with other Southeast Asian states, and illustrating that Jakarta is willing to inflict serious consequences on Beijing. More ambitiously, if it intends to react via deterrence by punishment, it can threaten to raise costs in several military and non-military means, including economic sanctions or military escalation. And of course, Jakarta need not be limited to this deterrence straitjacket and could mix these strategies with other approaches as well such as reassurance.

But the truth is that while these measures have been well known for a while, so have the challenges in actually implementing them. While the utility of various deterrence strategies continues to be a complex and contested affair, the success or failure of deterrence strategies hinges on a number of variables, including clarity, consistency, and capacity. But these are the very factors that have been lacking in Indonesia’s approach to the South China Sea, and they are due to the aforementioned structural challenges that remain, including Jokowi’s reluctance to adopt a more hardline overall stance against China and Indonesia’s limited military capabilities relative to what it would take to sustain a more confrontational approach toward Beijing. Beyond what Indonesia itself does, it bears noting that challenging China is no easy task even for countries with more capable militaries, with a case in point being Vietnam’s difficulties spotlighted during the oil rig crisis back in 2014, which, though eventually resolved, nonetheless came at a price for Hanoi.

Unless we see a fundamental change in these variables, chances are we are likely to see more continuity than change with respect to China-Indonesia tensions in the Natunas and beyond. And unless claimant states and interested actors prove increasingly capable and willing to take the actions necessary to deter future Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea, the signs are that Beijing is more than happy to continue with its current course.