Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some observers have drawn parallels between Russia’s aggression and certain seminal events in Vietnamese history, including the Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979. Some have even seen similarities between Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia to depose the brutal Pol Pot regime in 1978. One commentator has argued that the two conflicts have the “same basic dynamic.”

What is alarming, however, is that this belief has found strong roots in pro-Russia public sentiment in Vietnam.

And although not with the same intention, unfortunately, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has also invoked Vietnam’s occupation of his country more than 40 years ago in condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But is this analogy appropriate?

The World Knows Better

To compare the Russian aggression of 2022 to Vietnam’s intervention in 1978-79 is to ignore the humanitarian aspect of Vietnam’s casus belli and to perpetuate an obsolete Cold War mentality. The international community, conversely, has displayed the moral and legal capacity to perceive essential differences between the two conflicts.

In the case of the Vietnam-Cambodia war, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) was collectively aware of the horrors of the Pol Pot regime. Consequently, all its resolutions fell short of an express legal condemnation of Vietnam.

One of its first and most important resolutions dealing with the conflict, Resolution 34/22 (1979), described the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia as a “dispute” and urged “all parties to the conflict to settle […] by peaceful means”. The quasi-legal language usually employed by the UNGA in dealing with a state’s violations of international law, such as “deplore,” “condemn,” or “not to recognize” was absent from the resolution.

Even the name of the resolution, which referenced the “Situation in Kampuchea,” was very selective, although Vietnam had already taken Phnom Penh and, by that time, effectively controlled most of the country.

Between 1979 and 1989, 13 UNGA resolutions were adopted, and not one denounced Vietnam for violating the international norm of non-aggression. Moreover, the resolutions made no mention of “Vietnam,” employing instead terms such as “foreign forces” and “outside forces.”

This approach of the international community is radically different from its response to Russia’s actions.

In Resolution ES – 11/1 of March 2022, the UNGA categorized Russia’s conduct as “aggression,” stated that it “deplored” Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, and “demanded” the immediate cessation of unlawful activities in Donetsk and Luhansk.

Resolution ES – 11/4 of October 2022 specifically blamed the Russian Federation for the “illegal so-called referendums” and requested Member States “not to recognize” the “violation of the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine.”

The international condemnation of Russia has been plain, simple, and direct. The language employed illustrates the fundamental difference between the two interventions.

Human Rights and Humanitarian Evidence

In March 2022, the International Court of Justice requested that the Russian Federation further explain its arguments concerning allegations of genocide in Ukraine. Until that time, President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s ambassadors to the U.N. and the European Union, and the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation had circulated the narrative that their intention: “[was] to protect people who ha[d] been subjected to abuse and genocide by the Kyiv regime for eight years.”

However, when presented with official means of dispute settlement, Moscow has refused to provide any evidence, insisting instead that its “special military operation” was not relevant to the Convention on Genocide and is only relevant to Article 51 of the U.N. Charter and customary international law.

The Kremlin’s rhetoric of orchestrated Ukrainian “acts of genocide against the Russian-speaking population” is just one of many false claims in a global disinformation campaign against Ukraine.

In fact, after six years on the ground monitoring the human rights conditions of civilians in the contested area, specifically East Ukraine, the U.N. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that more human rights violations were committed by secessionist forces than by the Ukrainian government. More importantly, civilian deaths were carefully recorded, and show a significant downward trend, thanks to determined efforts to bring about a ceasefire.

Russia’s genocide rhetoric, with millions of lives at risk, was never supported by independent reports or acknowledged by international organizations.

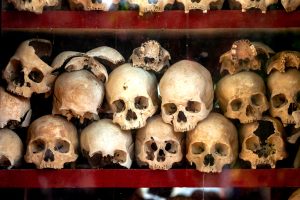

In contrast, by the time of Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia in December 1978, the atrocities of the Pol Pot regime, whether committed in Cambodia or Vietnam, were well known by the international community. As early as April of that year, the U.N. Human Rights Commission held public hearings, initiated investigations, and produced reports on conditions in Cambodia. Mass deportations, arbitrary killings, destruction of religious sites, and other crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge were all made known to the world.

Consequently, despite heated debates regarding the legality of Vietnam’s intervention during meetings of the Security Council and the UNGA – an outgrowth of the heated Cold War context in which the invasion took place – members of both Eastern and Western blocs repeatedly and unanimously condemned Pol Pot’s regime for its “sickening brutality,” “crimes of genocide,” and “contempt for human rights.”

The Vietnamese action constituted a rare historical event: it was, as Thomas G. Weiss commented, an intervention with a “very substantial humanitarian payoff,” even if the Vietnamese government did not, at the time, cite “humanitarian intervention” as the justification for its action. And this article does not intend to argue that the intervention was lawful per se under the lens of international law. Nonetheless, comparing this intervention to Russia’s war against Ukraine undermines the integrity of international institutions and subverts well-documented historical facts.