In the predawn hours of November 3, a boat with seven Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) members left a small island in the Sulu archipelago on a suspected kidnap for ransom operation. Locals had seen the group of unfamiliar men the day before and informed the security services. Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) forces intercepted the vessel in the darkness. It was fired upon by a helicopter before being rammed and split in two by a Philippine Navy vessel. An ASG leader, Mannor Sawadjaan, and the remaining six fighters were killed in the operation.

This dramatic nighttime encounter both demonstrates the increasing capacity of the AFP to counteract ASG activity in the maritime space and highlights trends and lessons learned that could be useful in informing the AFP’s continued efforts to combat ASG operations as they evolve.

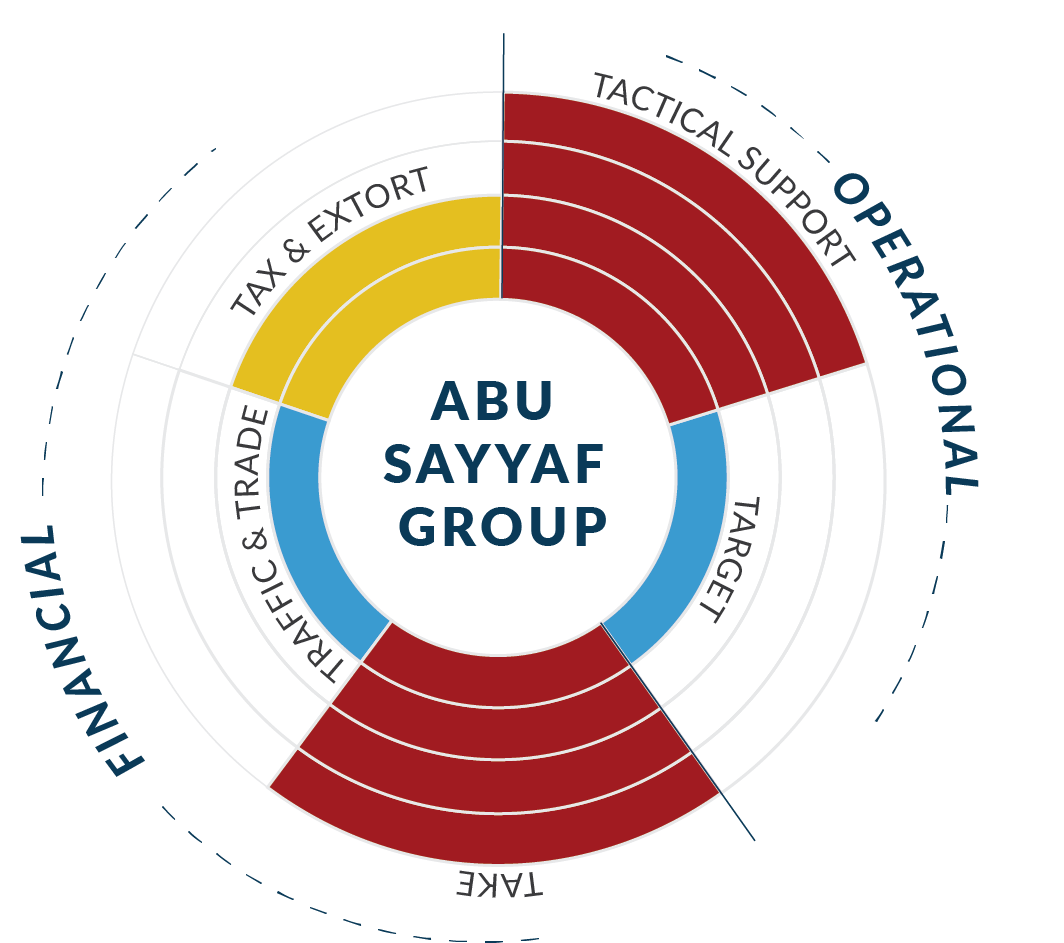

As demonstrated in the above infographic from Stable Seas’ recent Violence at Sea report, Abu Sayyaf Group’s maritime activities have largely been focused on piracy and kidnap for ransom (Take) and the movement of fighters and supplies (Tactical Support).

Civilians and HUMINT in Maritime Security

The first interesting component of this incident is the information collection that allowed it to unfold in the first place. Media reports indicate that local fishermen on Sulare Island saw the unfamiliar men in the area and reported their presence to authorities. While this may seem an insignificant detail, it highlights an extremely important, and sometimes overlooked, component of maritime security: civilians as a source of human intelligence.

Maritime domain awareness is critical to maritime security broadly and to combating the use of the maritime space by violent non-state actors like ASG. However, it is often discussed as an objective with largely technical (and expensive) solutions. The acquisition of assets such patrol vessels, aerial surveillance assets, and remote sensing systems is often framed as the singular means to achieving robust MDA. While such capabilities are extremely advantageous for MDA, this conversation sometimes overlooks another critical component, the role of civilians at sea and in coastal communities as a source of human intelligence.

The sea, particularly coastal and archipelagic waters, is not an empty space. A huge number and diversity of vessels operate around the clock and civilians on these vessels, as well as coastal communities that often rely on maritime industries, are acutely aware of the pattern of life in their local waters. As such, they represent a rich source of potential information for navies and maritime law enforcement agencies attempting to combat a variety of maritime security challenges.

However, in order to tap into this potential source of MDA, maritime security practitioners need to ensure two things: positive relationships with civilians in the maritime space and clear reporting tools when civilians detect potential suspicious activity at sea. If the relationship between maritime law enforcement and local civilians is contentious or punitive in nature there may be less willingness to cooperate with security services. If clear tools or procedures for reporting do not exist, civilians in the maritime space may simply allow suspicious behavior to go unreported.

This is no easy task as civilians may reasonably fear retribution for providing information. This being the case, two factors will need to be considered in order to ensure that this vital information can be collected. The first, and more narrow, requirement is that discreet mechanisms for reporting exist. Those with relevant information may be more likely to remain silent if reporting requires them to be seen meeting with the security services. The second and broader factor is the degree to which civilians feel safe from retribution should they provide information. Civilian protection in conflict settings is a difficult task in its own right and the need to consider it is a demonstration of the porous nature of criminality and political violence at sea and onshore.

ASG’s Geographic Dispersion

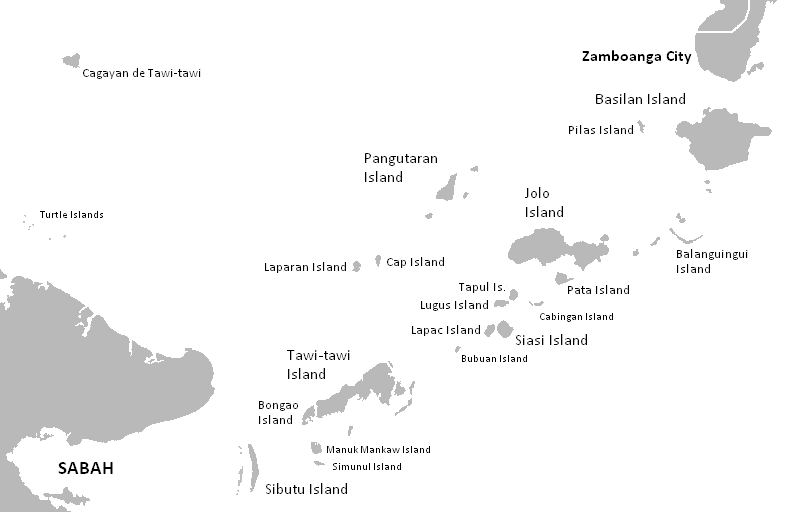

The second small but telling detail to be derived from this incident is its location. The epicenter of ASG activity recently has been Jolo Island, where AFP has been conducting a long string of operations against them. Since 2015, 54 percent of conflict incidents involving ASG recorded in the ACLED data set have occurred on Jolo Island. Over the course of the last year that has increased to 67 percent. However, the militants in this incident were intercepted operating off of Sulare Island, roughly 14 kilometers southwest of Jolo Island. Sulare is a very small island of only a few square kilometers. It is largely flat with a lagoon that covers a large portion of its surface area. Satellite imagery shows a small number of buildings and several small vessels along one section of the shoreline.

This information is important as it may be an early indication of a changing geographic distribution of ASG activity. As the string of recent operations on Jolo have put increased pressure on the group’s base of operation there, the use of such smaller, outlying islands as a launching point for ASG’s maritime operations may become increasingly appealing. Should this become an operational preference for the group, they have a variety of such launching points to choose from. Jolo is surrounded by many smaller islands of varying sizes and apparent population density at a similar distance from Jolo as Sulare.

Similarly, as the group becomes increasingly vulnerable on Jolo, it may seek to broaden its area of operations and target civilians across a broader geography. Subsequent incidents, such as the interdiction of a vessel carrying ASG members with small arms and explosives off of Zamboanga City by the Philippine National Police (PNP), suggest an even further geographic dispersion of ASG’s maritime operations. This may heighten the risk of potential attacks in maritime and coastal areas across the Bangsomoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

Geographically Dispersed Intelligence and Operational Presence

So how can both of these seemingly disparate observations inform future AFP efforts to combat the evolving threat of ASG operations in the maritime space? They may, in conjunction, point to a need for more dispersed operations and intelligence collection efforts beyond ASG’s recent area of operations on Jolo. As pressure mounts against the group there, the motives to exploit what are perceived as relative weak points in AFP presence may grow according. This could cause a shift to increased kidnap for ransom and terrorist attacks in the maritime space and the use of outlying islands for staging such activity.

In response to this shift, AFP should consider the options at its disposal for expanding the scope of its operations and intelligence collection to match the dispersion of ASG activity. Given the geography of the region and the resources available, this is a challenging task. The Philippine Navy, Philippine Coast Guard, and PNP Maritime Group already face pressures on the number vessels available for patrolling the maritime space. As such, a more semi-permanent, land-based presence in the form of small deployments of Philippine Marines on outlying islands around Jolo could be an alternative means for expanding presence into the areas ASG may be eying as potential new base areas for operations and denying them access. This would potentially deny the group new safe havens and help protect civilians in the areas where they may establish a presence.

Perhaps more promising though is the expansion of intelligence gathering efforts focused on these same areas. As was demonstrated in this most recent incident, civilians in these small island communities know when something suspicious is afoot. Building strong relationships between security services and these civilian populations and ensuring they can provide any relevant information discreetly and securely could help close off potential exit points and prevent more dispersed targeting of civilians by ASG as the pressure on them in Jolo mounts and they seek to diffuse their operations.

Jay Benson is the Indo-Pacific project manager at Stable Seas, a nonprofit research organization focusing on issues of maritime security and governance.